After 1949

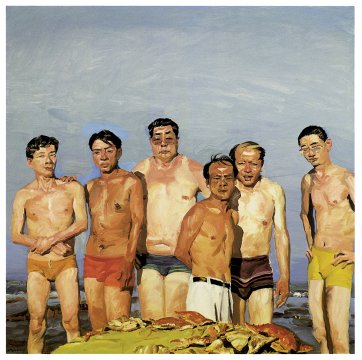

“Within the academy, figure painting was the foundation of art education and was the subject or motif that allowed artists to slide between classical, socialist and experimental modes of practice. Realism, and the centrality of figure painting within the French academic and Soviet traditions that had been introduced (beginning in the early 1900s), was thus the artistic foundation upon which the art of the immediate past was challenged.”

(Roberts C., Go Figure! Contemporary Chinese Portraiture, 2012)

After 1976

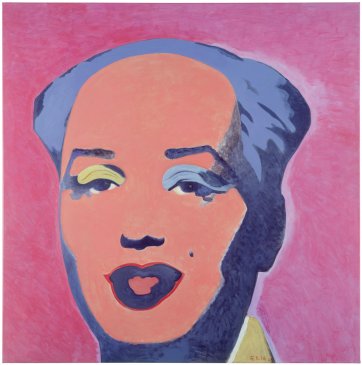

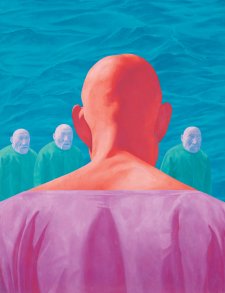

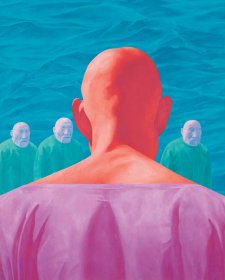

“The generation of Chinese who experienced the Cultural Revolution personally as teenagers tended to lapse into silence when they later came to reflect on their earlier fanaticism, since they were hard-pressed to deny the collective fervor behind it. But to the next generation unburdened by such memories, the thirty years since the founding of the Republic were a synonym for “absurdity,” and when they set about creating artwork, the first place they reached for inspiration was naturally the tableau with which they were so intimately familiar. The irony in such works tends to be forceful and obvious. Since all images in Chinese society had previously been painted according to a single aesthetic, and one that precluded criticism, artists of the 1980s, no matter what approach they took to depicting social realities, invariably perpetrate a sort of visual and conceptual assault that gives the viewer an impression of an attempt to satirize and destroy something rigid and ossified.”

(Zhang, Consuming the Absurd: Satire and humour in contemporary Chinese art)

“The majority of artists whose works are represented in this exhibition are the ‘lucky ones’ who came of age after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, and had the opportunity to attend university (they were closed during the Cultural Revolution), or were born in the decades thereafter. While still dependent on the state, those who passed the entrance examinations and entered China’s elite art academies, film schools and universities were able to escape into previously unimaginable worlds. Students engaged in wide-ranging experimentation and defined themselves as intellectuals, albeit of a new kind. After the chaos and trauma of the Cultural Revolution it was a privilege that came with the promise of a different and more self-directed future.”

(Roberts C. , Go Figure! Contemporary Chinese Portraiture, 2012)

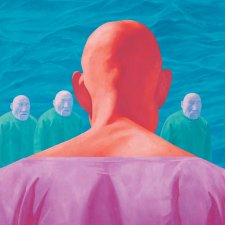

“For a thirty-year stretch, China was a society propelled by one utopian fantasy after another. The nation, the capital of Beijing, Tiananmen, the leaders’ compound of Zhongnanhai, the five-star red flag, the 10,000-li Great Wall, socialist communes—all served as spectral symbols, wreathing the leaders’ heads in divine halos. Political discourse extended down to the very foundations of society, such that people became accustomed to using this discourse to think about problems, and consequently became incapable of doubting the reasonableness of the reality they knew. Even their smiles all seemed to have been manufactured by the state—a uniform, proletarian smile that conveyed a purity, fixity, inimitability, and optimism and served the needs of the state propaganda machine. Adapted into various propaganda products, this smile was broadcast to every corner of the nation.”

(Zhang, Consuming the Absurd: Satire and humour in contemporary Chinese art)

After 1989

“Globalization precipitated Chinese artists’ turn to indigenous Chinese resources. If nation-building and nationalization were primary concerns of 1950s and 1960s, and modernization and belated enlightenment discourse dominated the 1980s, globalization was the new reality of the 1990s in China. The homogenizing force of transnational capitalism made its impact felt everywhere, including China. The inclusion of contemporary Chinese art works in international biennales and exhibitions and the Euro-American private and institutional interest in collecting them made the Chinese artists more conscious about their own standing vis-à-vis the international audience—real or imagined. Globalization prompted them to be more sensitive to their own indigenous cultural tradition on which they drew: both to stake out turfs of cultural identity and to have a competitive edge in the international market of ideas and “brands.” It is only to be expected that the recapitulation of pre-1949 Chinese images and motifs became a strategic way of staking out “Chineseness.”

(Wang, Three decades: Themes, 2012)

Further reading

Contemporary Chinese Art

www.88mocca.org

Andrews, J. F. (2008). Mahjong; Art Film and Change in China. (J. M. White, Ed.) Berkeley, California, USA: University of California, Berkely Art Museum and Film Archive.

Fan Di'an, (2011). A New Horizon; Contemporary Chinese Art. (Fan. Di'an, Ed.) Canberra, ACT, Australia: National Museum of Australia.

Fitzgibbons, A. (n.d.).

www.zhangxiaogang.org

Heinrich, C. (2005). Mahjong; Contemporary Chinese Art from the Sigg Collection. (B. F. Frehner, Ed.) Germany: Hatje Cantz.

Reifenscheid, B. (2008). China's Revision. (B. Reifenscheid, Ed., & L. C. White, Trans.) Munich, Germany: Prestel.

Roberts, C. (2012). Go Figure! Contemporary Chinese Portraiture. (C. Roberts, Ed.) Canberra and Sydney, Australia: National Portrait Gallery and The Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation.

Shen Kuiyi. (2008). Mahjong; Art Film and Change in China. (J. M. White, Ed.) Berkeley, California, USA: Univeristy of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific film archive.

Sigg, U. and Roberts, C. (2012, April). Go Figure! Contemporary Chinese Portraiture from the Uli Sigg Collection. Art in Australia.

Wang, E. (2012). Three decades/ Themes. Go figure! Conntemporary Chinese portraiture. (C. Dr Roberts, Ed.) Canberra and Sydney, Australia: National Portrait Gallery and The Sherman Contemporay Art Foundation.

Wu Hung. (1999). Transience; Chinese experimental art at the end of the twentieth century. Chicago: The David and Alfred Smart Museum.

Zhang Letian. (2012). Consuming the absurd: Satire and humour in contemporary Chinese art. Go figure! Contemporary Chinese Portraiture. (C. Roberts, Ed., & C. G. Rea, Trans.for Zhang, L.) Canberra and Sydney, Australia: National Portrait Gallery and The Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation.