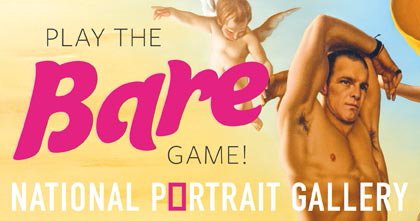

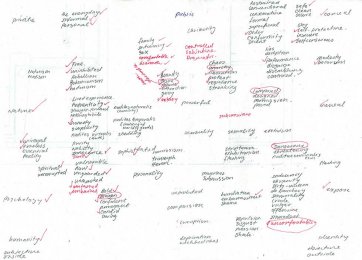

While I was curating Bare: Degrees of undress I did keep detailed records and this piece is an attempt at such a statement. Like a kind of reverse blog, it narrates and reflects on how Bare came together, the decisions that were made and the thought behind the exhibition. In retrospect, it shows how I experience curation as a strange process of discovering what is already there. Even in an exhibition so seemingly actively arranged and interpreted, the process for me was one of recognising when patterns, themes and ideas emerged for themselves. Curating was noticing.

How it began

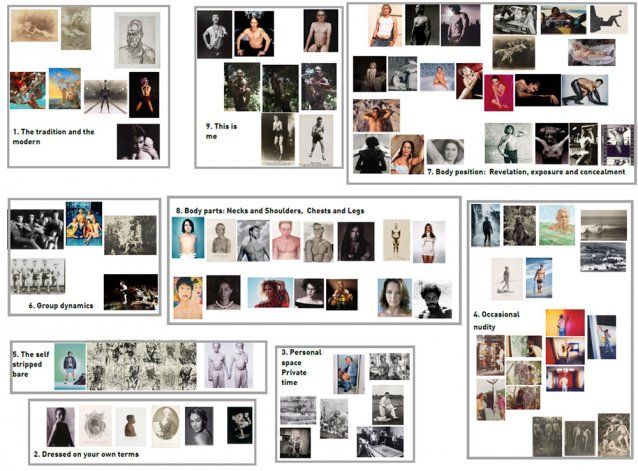

The exhibition includes ninety of just over a hundred portraits – about 4% of the collection – that reference dressing, undressing or being undressed. The survey of the collection was initially done by India Bednall, a Curatorial Intern in 2013. I asked India to think back on her time at the Gallery and she wrote to me from London:

In July 2013, I was fortunate to undertake a 20-day curatorial internship at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra as part of my Masters of Art Curatorship program at the University of Sydney. My project involved researching the collection, specifically looking for portraits containing nudity, and then writing some articles based on my findings. This was of particular interest to me as the year before I had studied the artistic nude in depth, writing my Honours thesis on the nudes of Edgar Degas. I was intrigued to see how nudity gains deeper meaning in the context of a portrait, where the identity of the subject is known.

After a week of trawling, I found there weren't that many nude portraits in the collection. This was understandable, as nudity is often more palatable when paired with anonymity in art. What I hadn't anticipated finding was a spectrum, on which nudity was merely an extreme. My research expanded to encompass all portraits depicting subjects in various states of undress. I became fascinated with the different meanings conveyed by degrees of bareness in portraits. I discovered that the identity of the sitter - whether actor, musician, model, sportsperson, or national personality - was important to how the bareness was interpreted. Equally, I saw that the sitter's willingness to be depicted in a state of undress conveyed something about their identity.

My four weeks in Canberra flew by, and the project became a subject I was passionate to pursue in future studies.

A year out – a gap in the program and ‘Australians Unclad’

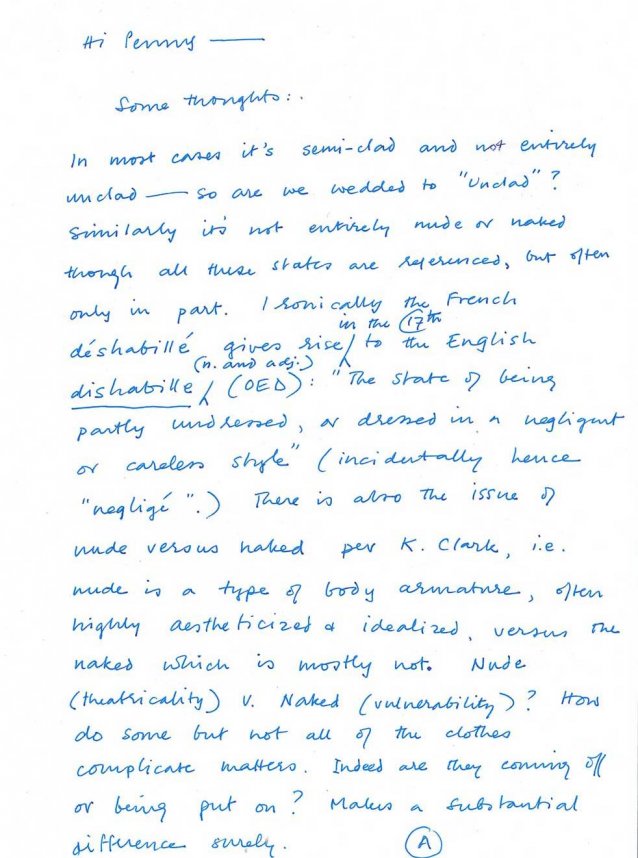

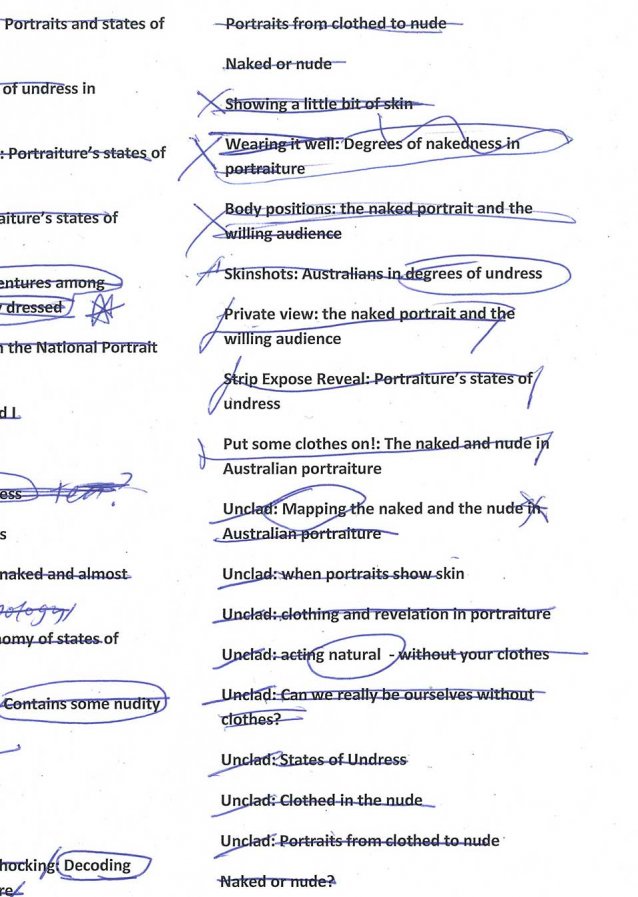

As sometimes happens in a gallery’s schedule, a window opened up and India Bednall’s conceptually solid and intellectually rigorous exploration of the collection was not only the bones of a show but most of the flesh and feathers as well. Most exhibitions are developed over two to three years. The lead-time for this one was much shorter – about nine months, but with the bulk of the work concentrated in the last six months. I came up with the working title of ‘Australians Unclad’ and wrote this in the ‘Exhibition Brief’:

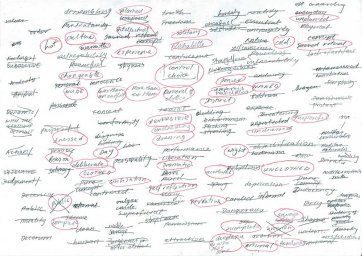

Description: Invites the visitor to think about portraiture in a new way as the exhibition foregrounds the subjects’ state of undress as its organising principle. The visitor’s focus will be immediately thrown to the form of the representation and its relationship with identity rather than accessing the portraits through the person’s biography. Unlikely parallels will form in a display that will be out of chronological sequence and cultural theme. Registering and confronting their reaction to the exposed body prompts three important lines of reflection on portraiture:

-

the contested gaze – the visitor’s own personal curiosity, empathy, admiration, desire, shock or revulsion

-

the social, cultural and personal politics of representation in the context of society’s mores, expectations and conventions

-

identity’s grounding in the space between the public and the private self – brought to the fore as the private body is brought into the public space of a portrait

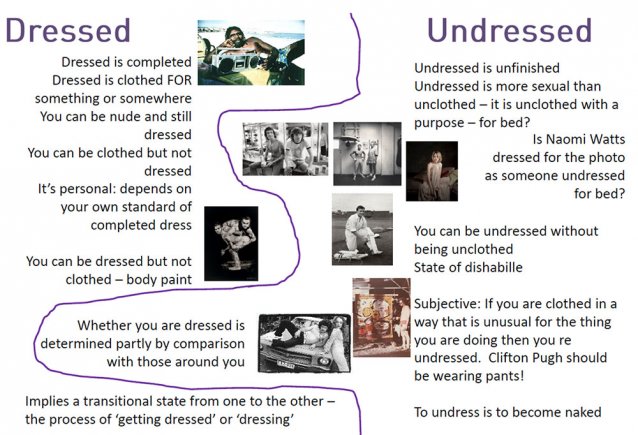

It is well recognised that clothing and fashion communicate something in a portrait, but the lack of it also does, carrying its own range of statements about the person. Exposed skin, because of the conventions of our society, is in many ways a stronger, more emphatic statement than covered skin.

Sources: the well-trodden path and verge not trampled

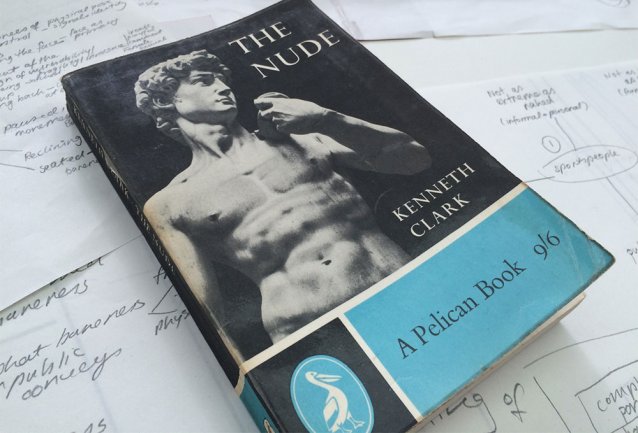

The initial aim was for the exhibition to be intelligent, fun and engaging but not overly discursive, didactic or academic. We also wanted to present our collection in a fresh way. A huge amount has been written on the nude in art, one task was to chart a path through this literature. It was important to acknowledge this context in the exhibition without covering every inch of wall with text.

The distinction between the naked and the nude has an entire literature of its own and I referenced this in the exhibition by including in the introductory text the first stanza of The naked and the nude by the British poet Robert Graves. Famous as a World War I poet and author of the classic autobiographical novel Goodbye to All That, Graves also authored the novel I, Claudius and its sequel, which was adapted into an internationally hit TV series in the 1970s. Graves’ poem bears the same name as Walter Sickert’s famous rant on the subject in 1910 in The New Age: ‘The nude has taken on with time some of the qualities of an examination subject … An inconsistent and prurient puritanism has succeeded in evolving an ideal which it seeks to dignify by calling it the Nude, with a capital “n,” and placing it in opposition to the naked.’ Railing against the fashion of ‘drawing from life’ Sickert observed: ‘I would wager that the major part of these enthusiasts could not put on paper a respectable drawing of a boot-jack or a gingerbeer-bottle, both of which at least keep still.’

The naked and the nude, by Robert Graves

For me, the naked and the nude

(By lexicographers construed

As synonyms that should express

The same deficiency of dress

Or shelter) stand as wide apart

As love from lies, or truth from art.

Lovers without reproach will gaze

On bodies naked and ablaze;

The Hippocratic eye will see

In nakedness, anatomy;

And naked shines the Goddess when

She mounts her lion among men.

The nude are bold, the nude are sly

To hold each treasonable eye.

While draping by a showman's trick

Their dishabille in rhetoric,

They grin a mock-religious grin

Of scorn at those of naked skin.

The naked, therefore, who compete

Against the nude may know defeat;

Yet when they both together tread

The briary pastures of the dead,

By Gorgons with long whips pursued,

How naked go the sometimes nude!