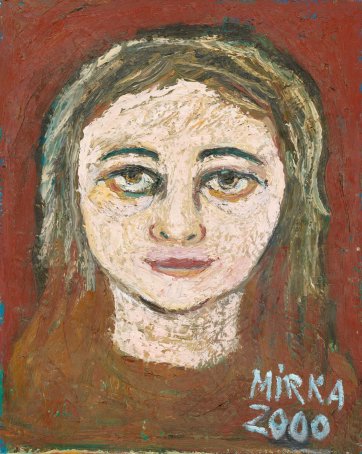

Mirka Mora’s influence on Australia’s cultural and culinary scene both as a contemporary artist and one of Melbourne’s most loved restaurateurs remains widely felt today. Born in Paris, Mirka immigrated to Australia with her husband Georges and their son Philippe in 1951, settling in East Melbourne and becoming deeply entangled within the local art scene. Portraits of Mirka in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection show the multifaceted span of the artist’s career, capturing her zest for life and dynamic personality.

In photographer Lazar Krum’s portrait Mirka – 9 Collins Street (c. 1966), the artist stands in front of one of her distinctive murals at her inner city studio/home. Taken about 15 years after immigrating to Melbourne, Krum provides us with a snapshot of Mirka’s life. Behind the artist we can just make out a mural with the interwoven motifs of angels, wide-eyed children, animals and hybrid creatures that became iconic symbols of her practice. Drawing from memories of childhood innocence, cut short by the outbreak of the Second World War and a narrow escape from Auschwitz, Mirka’s works unpack love and loss, and celebrate humanity and resilience. As Krum has suggested, his image ‘captured Mirka, in the midst of her iconic faces, caught between both the delightful and ominous nature of her life experience’.

Soon after their arrival in Melbourne, Mirka and Georges moved into an empty sculptor’s studio in Collins Street. They became involved in the revival of the Contemporary Art Society, befriending art patrons John and Sunday Reed and members of the Heide group including Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd, Albert Tucker, Joy Hester, John Perceval, Charles and Barbara Blackman. Defying rigid social norms and behaviours, the Reeds championed a break from the traditions of artistic conservatism, encouraging the experimental and modernist work of the Heide circle. Mirka’s love for Paris, cosmopolitan ideas and European style were infectious, and she and her husband were quickly absorbed into the avant-garde group.

Mirka’s charisma, generosity and charm created the perfect environment for Mirka Café, which the couple opened in 1954 on 185 Exhibition Street. Introducing European-style dining to 1950s Melbourne – the Moras were pioneers in introducing outside seating to the urban environment and their café was allegedly the first to sell espresso machine coffee – Mirka Café became a hub for artists, collectors, writers and other well-known figures. Due to its popularity, the café soon outgrew its location and in 1956 Mirka and Georges opened Café Balzac in Wellington Street, East Melbourne. The first restaurant in Victoria to receive a 10pm liquor license, the Balzac became known for hosting leading modernist artists and their works, including John Perceval’s infamous angel series which the Moras commissioned for the walls of their restaurant. The Moras sold the Balzac in the late 1960s, and subsequently bought the Tolarno Hotel in St Kilda, opening the Tolarno French Bistro and later Tolarno Galleries, which became a major landmark for the progression of modern and contemporary Australian art. The Tolarno also housed the couple, their three sons Philippe, William and Tiriel, as well as a large studio space for Mirka.

Embracing a modern lifestyle outside the boundaries of prescribed gender roles, Mirka assisted with the running of the restaurant, while juggling her artistic career and raising their children. She hand-painted the walls of the Tolarno bistro, hallway and bathrooms with whimsical and colourful large-scale murals, featuring her characteristic fantastical beings inspired by fairytales, Eastern European folk art, classical mythology, childhood memories and her active imagination. In a society deeply rooted in misogyny, she used textiles and craft to create quintessentially feminine works that employed traditions of craft making and unconventional modes of making, integrating textiles, soft-sculpture dolls, mosaics, works on paper and paintings. Although Mirka took a non-political stance towards feminism, her works subsequently challenged the hierarchy of western art historical discourse that favoured painting and sculpture as visual mediums.