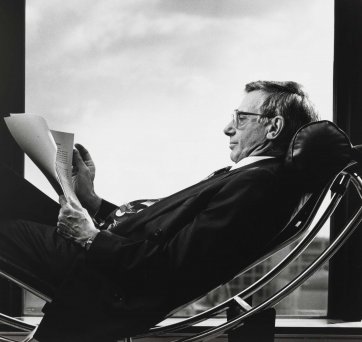

Alan Goldberg, 2014 Jacqueline Mitelman. © Jacqueline Mitelman

This portrait of Alan Goldberg AO QC was captured by renowned Australian photographer Jacqueline Mitelman in 2014. The work was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery the following year, an addition to the Mitelman portraits held by the institution which now (August 2021) number 23 photographs of remarkable Australians, spanning several decades. In the image, a worn armchair frames the background, from which there emerges a relaxed face and subtle smile. It’s a warm expression so familiar to me, as it’s that of my late grandfather. Dressed in a black suit and sporting a colourful bow tie, Alan exudes humanity and formality in equal measure.

The following essay is an edited version of a larger research piece I recently compiled on my grandfather. As a child, I was enthralled with my Papa Alan, though I was unable then to comprehend the enormity of his professional life. In late 2018, this led me to interview past friends and colleagues, search library collections, and scour court registers. Courtesy of Alan’s meticulous record-keeping – he archived every document, photo, letter and speech – I also came across school reports, childhood photos, newspaper clippings and other ephemera to draw on. It’s been a gratifying mission, both for me and my extended family, yielding new insights into the character behind that blue and gold bow tie.

A fifth-generation Australian, Alan Henry Goldberg was born in Melbourne on 7 August 1940 to Margery and Geoffrey Goldberg. He excelled through his primary and secondary education, going on to attend Melbourne University, a crucible of intellects in the late-1950s. It was here that Alan met Ron Castan, Jack Fajgenbaum and Ron Merkel. The group would become lifelong friends, as well as luminaries of Australian law. Alan, Ron Castan and Jack would study at one another’s houses most Sunday nights, with the work interspersed with political debate and robust religious and philosophical discussion. The trio went on to graduate as the top three students in their class – Ron first, Jack second and Alan third.

1 Melbourne University study group, c. 1959 [Ron Castan and Alan Goldberg on left]. 2 Alan’s graduation from Melbourne University, c. 1962 [L-R: Jenny Goldberg, Alan Goldberg, Margery Goldberg, Geoffrey Goldberg].

Ron Merkel graduated some years behind Alan at Melbourne University. When I met with Ron, he laughed that his university success was (at least in part) attributable to Alan – in his second year Ron’s summaries of Alan’s legal notes had secured him the Tort Exhibition, which happened to come with the most money of all academic prizes.

Soon after graduating, Alan was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to Yale University – not too far from Ron Castan, who was at Harvard, and Jack Fajgenbaum, at the University of Chicago. Alan arrived at Yale in the 1960s, as a new era of social consciousness, led by the civil rights movement, was emerging against the stark backdrop of racial injustice. It was to be a critical, formative time in Alan’s life, informing his outlook and career progression. In a 2015 interview, Alan recalled the socio-political turmoil of the times as deeply confronting, and that he ‘suddenly became alerted or invigorated with the wrongness of what was happening’.

1 Alan’s graduation from Yale University, 1964. 2 Yale University Graduation Book, 1964 [Alan bottom-right].

Alan returned to Australia in 1964 to be admitted to the Bar, and, several years after this, married Rachel Rynderman. Alan laughed that it was the Bankruptcy Act that brought the pair together. At the time, Rachel was a social worker for the Red Cross and had a client who was filing for bankruptcy. Unfamiliar with the relevant laws, Rachel phoned Alan for advice, with the call ending in plans for dinner later that night. The subsequent periods of ‘keeping company’, as Alan described them, led to marriage in December 1967, and a loving 49-year union.

1 Alan and Rachel on their wedding day, 1967. 2 Ron Castan, 1996 Francis Reiss. © Estate of Francis Reiss.

Forever moved by his 1960s experiences, Alan was drawn to numerous issues concerning civil liberties throughout his life and career. The 1985 ‘Your Rights’ matter was, literally, a case in point. Your Rights was a yearly publication issued by the Council for Civil Liberties (an organisation of which Alan was later president), and its tenth iteration included a chapter, added by the head of the Council, questioning the validity of the Holocaust. As Jews, the chapter was a personal affront for Alan and Ron Castan, but they also found the concept of Holocaust-denial in a publication purporting to represent ideals of civil liberty to be obscene. They challenged the dissemination of the publication in the Federal Court of Australia. Ron articulated their case with a simple analogy: ‘You can’t put rat poison in Kellogg’s Corn Flakes and call it “Kellogg’s Corn Flakes”. So you can’t put Holocaust denial into this book and call it civil liberties.’ Although the court did not rule in Alan and Ron’s favour, their case was substantively successful in that it drew significant media attention, which later pressured the head of the Council to step down.

A subsequent career highlight saw Alan act as Senior Counsel for Tasmanian gay rights activists Rodney Croome and Nick Toonen. In this landmark 1995 human rights case, Alan represented the pair in their effort to repeal Tasmania’s anti-homosexuality laws, which criminalised private sexual activity between consenting same-sex adults. As Croome and Toonen were unable to obtain legal aid – a controversial issue, as their application was understood to fulfil the requisite funding criteria for a public interest case – Alan offered his services pro bono. His efforts were critical in bringing about the 1997 Criminal Code Amendment Act that rescinded Tasmania’s anti-homosexuality laws.

1 Portrait of Alan, c. 1985. 2 Alan sitting at his desk at Aickin Chambers, Melbourne, c. 1990.

Alan was appointed Judge of the Federal Court of Australia in February 1997, a momentous development in his career. Seven years into his tenure, he was given the mammoth task of hearing all legal disputes surrounding the collapse of Ansett (Australia’s then second domestic airline). Through Alan’s judgements, the administrators were successful in recovering sufficient funds to pay all of Ansett’s employees their entitlements. These judgements were highlights of Alan’s judicial career, and led directly to amending the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Alan directed and approved the administrators to disseminate the notice of a creditors meeting via a website and hotline, in place of printing and mailing each report individually. This saved Ansett some $23 million. In 2007, the legislative change allowed the dissemination of creditor-relevant information by electronic means. This is fondly referred to as the ‘Goldberg Ansett Amendment’.

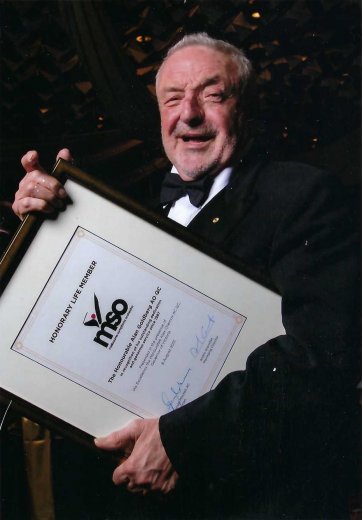

1 Alan’s appointment as judge at the Federal Court of Australia, 1997 [Alan sixth from the right]. 2 Award of Life Membership of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra August, 2013.

Being Jewish was entrenched in Alan and Rachel’s life. Although they were not spiritually devout people, like many they drew their connection to Judaism through community. Alan sat as an advisor to two leading Jewish day schools – Bialik College, of which he was also a ‘visiting educator’, and Mount Scopus Memorial College. Alan’s love of community also saw him pursue broader cultural engagement; from 1987 he served on the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s (MSO) board and advisory committee, and later became its Vice-Chairman. In recognition of his time and work with the MSO, Alan was awarded a Life Membership in 2013, an honour shared with only one other individual at the time, Sir Elton John. He also served as an inaugural Board Member of the TarraWarra Museum of Art from 2000 to 2015.

Alan retired as a judge from the Federal Court in June 2010. Leading the ceremony at his farewell was then Chief Justice of the Federal Court, Patrick Keane AC, whose opening words were instructive: ‘The sobering reality of this occasion is that Justice Goldberg’s culmination of legal learning, energy, imaginative insight, sense of duty, wisdom and fundamental decency is such that I teeter on the edge of despair at the thought of the difficulty of finding a replacement. This combination of qualities is such as to make him, I fear, virtually irreplaceable.’

Alan passed away in 2016, having lived courageously with Parkinson’s disease, diagnosed in 2004. In my research, I asked regularly about Alan as an individual, transcending professional accomplishments alone. A past colleague lauded Alan as unobtrusively influential. Another praised him as having great judgement and infinitive wisdom. A universal theme was Alan’s charm, patience and kindness. When I met with Ray Finkelstein AO QC and Michael Black AC QC at Castan Chambers – in a place and in the company of people so dear to Alan – I observed quintessential nostalgia: two people smiling and reminiscing about a beloved friend and colleague. They also reiterated my experience – that in all conversations about Alan, interviewees would reflexively mirror his engaging, warm disposition.

In 2015, Melbourne University instituted the Alan Goldberg AO QC Scholarship, and, later, boardrooms at Castan Chambers and Arnold Bloch Leibler were posthumously dedicated in his honour. I hope the scholarship’s recipients and boardrooms’ residents might also come to know of Alan’s qualities, so fondly remembered by his friends and associates. For my part, my research helps complete a picture, started with fond memories of a grandfather’s regular Friday night bedtime stories to his five grandchildren, which always emphasised the fundamental importance of being good people and having good values. I see it as only fitting that I share these insights with the National Portrait Gallery, to accompany the Gallery’s own picture of Alan, a portrait which, with its becoming mix of formality and warmth, lends itself to further storytelling.

![Melbourne University study group, c. 1959 [Ron Castan and Alan Goldberg on left] Melbourne University study group, c. 1959 [Ron Castan and Alan Goldberg on left]](/files/3/4/7/c/i15243-th.jpg)

![Alan’s graduation from Melbourne University, c. 1962 [L-R: Jenny Goldberg, Alan Goldberg, Margery Goldberg, Geoffrey Goldberg] Alan’s graduation from Melbourne University, c. 1962 [L-R: Jenny Goldberg, Alan Goldberg, Margery Goldberg, Geoffrey Goldberg]](/files/3/a/f/0/i15244-th.jpg)

![Yale University Graduation Book, 1964 [Alan bottom-right] Yale University Graduation Book, 1964 [Alan bottom-right]](/files/8/f/1/a/i15246-th.jpg)

![Alan’s appointment as judge at the Federal Court of Australia, 1997 [Alan sixth from the right] Alan’s appointment as judge at the Federal Court of Australia, 1997 [Alan sixth from the right]](/files/d/a/7/1/i15249-th.jpg)