In the 2006 film Night at the Museum, a newly-recruited night watchman discovers that the natural history exhibits he guards come to life when visitors leave for the day. Chaos inevitably ensues. There’s a fire, an escape, and a crazy chase, but eventually order is restored. It was a film never destined to figure in Oscar conversations, but it plays with an intriguing fancy that dates back to Frankenstein: what happens when inanimate objects are animated?

Traversing similar territory (but eschewing the chaos!), In their own words brings a new dimension to the National Portrait Gallery Collection by allowing the portraits to speak. As we gaze at the faces on display, either in the Gallery or online, we can – via a new, purpose-developed mobile app – hear the voices of the subjects and the artists. The stories and observations they share, and the tone and timbre of their spoken words, give us a fresh insight into their identity and their passions; in effect, it constitutes a rich aural portrait to complement the visual.

This unique project began in 2018 in a groundbreaking collaboration between the Gallery and the National Library of Australia. Most of the recordings to date are drawn from the Library’s Hazel de Berg collection, a priceless repository of nearly 1300 oral histories of notable Australians gathered between the late 1950s and the early 1980s. De Berg recorded the life stories of people born between 1865 and 1953 – some towards the end of their illustrious lives, others just starting to make their mark in their field of endeavour. Artists make up the largest group, but de Berg also sat down with writers, scientists, politicians, historians, dancers, architects and film directors.

1 Barry Humphries, 1958 Clifton Pugh AO. © Shane Pugh. 2 Head study for portrait of Margaret Olley, 1994 Jeffrey Smart AO. © Estate of Jeffrey Smart.

My first task (with the help of Gallery curators and Library researchers) was to match de Berg’s subjects with portraits in the Gallery’s collection. Initially, when we envisioned the audio guide as an in-Gallery experience only, we chose subjects that are more commonly on display – more robust works such as oil portraits and sculptures. That included, for example, Clifton Pugh’s 1958 portrait of Barry Humphries, who reminisces about his university days in Melbourne. ‘I was merely a frustrated youth, not at all knowing how best to please my parents’, Humphries says. ‘What profession indeed I would ever follow and when was it all going to end?’ When we realised the Gallery’s intrepid digital partner Stripy Sock was creating an app that could be used anywhere, it meant we could include more fragile works less likely to be physically displayed, such as Jeffrey Smart’s pencil sketch of Margaret Olley, who talks, as a young woman, about her many ways of working: ‘I might make little thumbnail notes but never very detailed, because I feel you kill the painting you want to do’.

The shortest de Berg recordings are less than ten minutes, while others run for several hours. When choosing audio excerpts for the project I limited each to no more than two minutes. I would read the transcript, pick out a section that was particularly interesting, surprising or enlightening, then listen to and edit the recording. Sometimes, as with brilliant jazz musician (and equally wonderful raconteur) Don Burrows, it was impossible to choose just one excerpt. For him I chose three, and we included them all. He tells us that he started making music with his mother’s upturned saucepans and cake tins, and when he was given a B-flat flute at school ‘it was the equivalent of handing a violin student a Strad[ivarius]’.

1 William Bligh, c. 1776 John Webber, Currently on display. 2 Lola Montes, c. 1845 Joseph Karl Stieler.

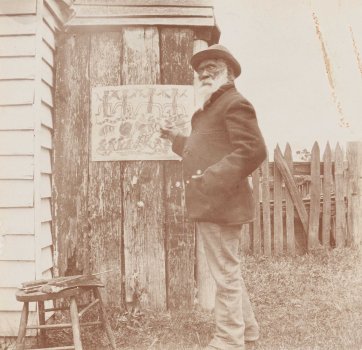

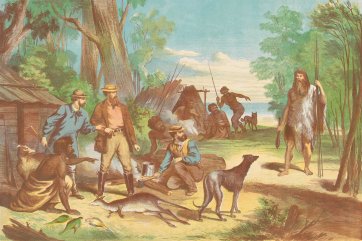

As the project progressed, we included subjects who were around before audio recording was possible or common. To enable the portraits of people such as William Bligh and Lola Montez to ‘speak’, I found personal narratives in diaries, letters, journals and newspaper articles that were then voiced by actors. For the portraits of esteemed Wurundjeri Elder and artist William Barak (1824-1903), his words, from a transcript of an oral history he dictated late in his life, were read by current day Wurundjeri Elder Uncle Colin Hunter. Barak recounts meeting, as a child, John Batman and the escaped convict William Buckley.

1 William Barak at work on the drawing ‘Ceremony’ at Coranderrk, 1902 Johannes Heyer. 2 Buckley discovering himself to the early settlers, 1869 S Calvert, Gibbs, Shallard and Co after O.R. Campbell.

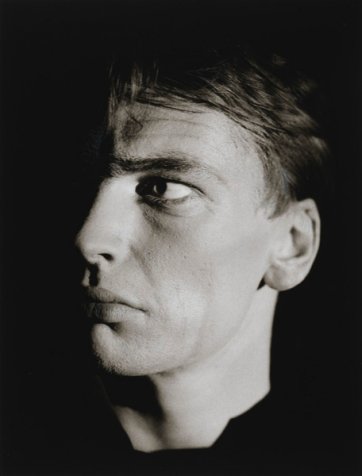

So, who were my favourites out of the 160 or so I worked on? The short answer: whoever I was working on at the time! But there were some real ‘ah-ha’ moments – for example, when I heard the then young actor and director John Bell tell de Berg in 1974, ‘I can’t think of anything that would please me more than a more or less permanent Shakespeare company of my own, not just playing Shakespeare but making that the basis of our work’. We know that he went on to found the Bell Shakespeare Company in 1990, but back in 1974 it was still just a dream. This audio excerpt also beautifully matches the portraits of Bell in our collection: Jozef Vissel’s 1962 photographic portrait shows a determined young man (with his eye on the prize?), while Nicholas Harding’s work, created nearly 40 years later, depicts Bell as a grizzled King Lear.

1 John Bell, 1962 (printed 2006) Jozef Vissel. © Jozef Vissel. 2 Study for John Bell as King Lear, 1998-2001 Nicholas Harding. © Nicholas Harding.

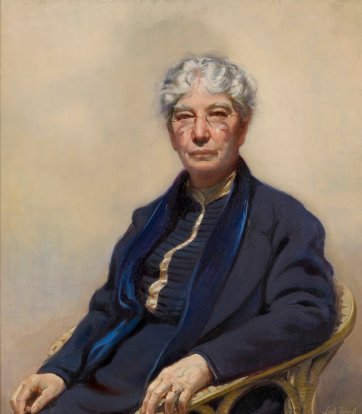

I adored hearing the voice of Dame Mary Gilmore, the great poet, journalist and radical social visionary, recorded just a few years before her death in 1962. In her 96th year, she recollected the many changes over her long life. There’s an older person’s sibilance in her speech but her voice is strong and true. The Gallery has three portraits of Gilmore: Lyall Trindall’s 1938 oil painting shows her imperious and unflinching; in a 1950s photograph she’s alongside fellow legends, Doc Evatt and Albert Namatjira; while Max Dupain’s portrait depicts her as she was around the time of the de Berg recording.

1 Dame Mary Gilmore, 1961 Max Dupain OBE. © Max Dupain/Copyright Agency, 2024. 2 Dame Mary Gilmore, c. 1938 Lyall Trindall. © Estate of Lyall Trindall. 3 Dr HV Evatt, Albert Namatjira and Dame Mary Gilmore having a meal, c. 1950s an unknown artist.

Sometimes the contrast between the portrait and the audio story is shocking – in a most delightful way. Henry Robertson Smith’s 1853 portrait of David Jones shows the colonial merchant and department store founder as a respectable older gent, sporting spectacles and a black suit with a newspaper spread on his lap. But the narrative, voiced by actor Christopher Baldock, tells a different story. We hear Jones’ account, in an 1838 letter to The Sydney Gazette, of how he was forced to engage in fisticuffs when confronted by a displeased business partner, leading to an assault charge. ‘Had I not sufficient provocation?’ Jones pleads.

1 David Jones, 1853 Henry Robinson Smith. 2 Maie Casey, 1953 an unknown artist.

There are many more wonderful stories. Governor’s wife and aviatrix Ethel ‘Maie’ Casey wonders why artists don’t paint ‘landscapes of the air’ – clouds seen from above. Thea Proctor muses on the forces that create an artist: ‘I think it is an overwhelming love of beauty which causes anyone to become an artist, an extra sensitiveness to line and colour, as musicians are sensitive to sounds’. Novelist Robert Drewe draws on his own experience to advise that he doesn’t think ‘journalist training does any harm to writers, as long as they get out of it virtually unscathed by the time they’re about 30’.

1 Self portrait, 1921 Thea Proctor. © Art Gallery of New South Wales. 2 Robert Drewe (in the swell), 2006 Nicholas Harding. © Nicholas Harding.

In their own words is an ongoing project; it will be added to over time to include recordings from the Gallery’s own Portrait Stories collection, and oral histories and interviews from other Australian archives. In the meantime, download the app and run riot through the sounds and stories of these exceptional Australians.