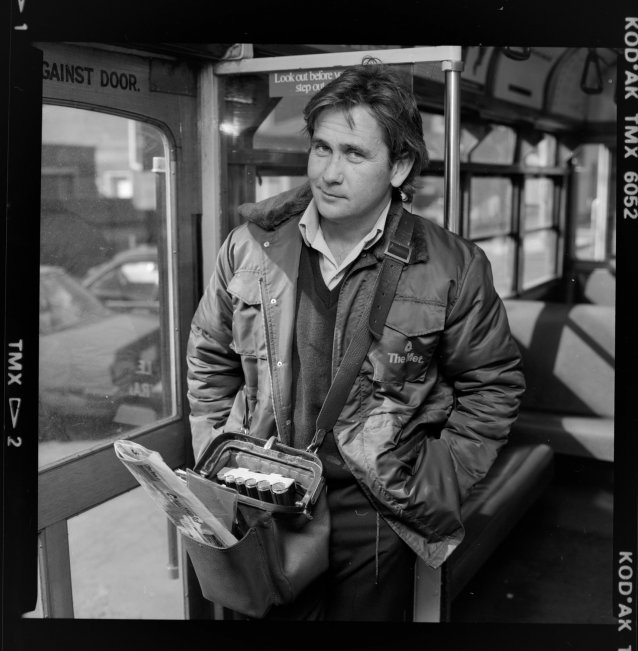

Around the corner from student photographer Matt Nettheim’s dilapidated Melbourne share house lay the Malvern Tram Depot. One day, camera in tow, he started hanging around, sensing the potential for some experimentation with lighting and composition. After a few months, having gained acceptance (unofficially) and permission (officially), Matt began heading out on the trams and asking the conductors if they’d pose for a portrait. It was 1990.

Matt was in the second year of his fine arts degree – majoring in photography – at Victoria College, Prahran Campus. Numerous artists represented in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection either taught or studied at this legendary college, including Athol Shmith, Carol Jerrems, and John Gollings. Matt was one of the last students to graduate under esteemed photographer and educator John Cato, whose eleven years as head of the photography department was coming to an end. With the aspiring photographer required to submit portfolios of his work each term, the depot and its people became his subjects.

The last time I chatted with Matt was in a 2018 public conversation at Adelaide’s Samstag Museum of Art, as we discussed the NPG’s touring exhibition Starstruck: Australian Movie Portraits. His motion picture stills photography work featured prominently in the show, with images from Rabbit Proof Fence (2002), Somersault (2004), Jindabyne (2006), and The Eye of the Storm (2011). More recently he’s shot the stills for Jennifer Kent’s The Nightingale, the Storm Boy remake, and Tim Minchin’s television series Upright.

This time – mid-June 2020 – I spoke to Matt by phone. With the film industry (and consequently his everyday work) at a standstill as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown measures, he was at home in Baudin Beach on Karta (Kangaroo Island). He’d been going through his archive and working towards a book, which is what led to him revisiting the tram portraits. ‘In hindsight,’ he mused, ‘I became kind of like an artist in residence at the Malvern depot’.