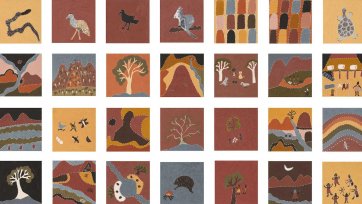

In this prominent location, Ngaalim-Ngalimboorro Ngagenybe (From my women) frames the National Portrait Gallery’s collection through a lens of contemporary portraiture, inviting the viewer to consider the underlying ideologies of the genre. Portraiture comes from a western tradition of representation and expression, and its conventions are historically informed by western notions of identity and personhood. While some artists actively challenge the conventions of portraiture and stereotypes through their practice, Purdie’s approach to portrait-making quietly expands the genre.

Ngaalim-Ngalimboorro Ngagenybe was created for the 2018 exhibition So Fine: Contemporary women artists make Australian history, in which curators Sarah Engledow and Christine Clark invited ten artists to reflect on and reinterpret Australian history through contemporary portraiture. In September 2019 the self-portrait was acquired for the Portrait Gallery’s collection, an acknowledgment of Purdie’s personal history as a crucial part of the Australian experience, and one that will become increasingly important in the national conversation around cultural life and national identity. This landmark addition to the collection enhances the Gallery’s capacity to engage with Aboriginal ways of seeing and understanding the world, as well as making an important contribution to the genre of portraiture more broadly.

Interrogating portraiture and supporting artists to challenge its boundaries is one of the responsibilities of a national portrait gallery. Inaugural National Portrait Gallery Director Andrew Sayers described the unique position in relation to Australian identity, stating, ‘National portrait galleries have been traditionally predicated on the idea that identity can be equated with individuality. In Australia, however, we have Indigenous traditions in which identity is actually lodged somewhere else – in relationships and in people’s relationships to land.’

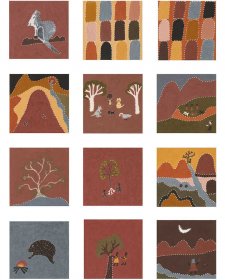

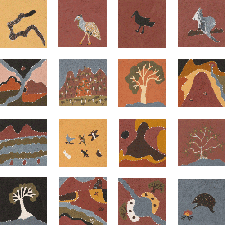

In Ngalim-Ngalimbooroo Ngagenybe, Shirley Purdie pays homage to the women in her family, representing herself through their collective knowledge, culture and values. Her self-portrait depicts someone who has lived a storied life, shaped by land, family, law, ceremony and language. Unlike a traditional western portrait, these significant women are represented through their relationships and their stories rather than their physical appearance.