In late February of this year, the COVID-19 crisis began to fill our screens with a maelstrom of images: healthcare workers in hazmat suits, and well-dressed Italians in increasingly empty streets, faces obscured by personal protective equipment (PPE). The face mask became the new constant, and brought with it a striking irony. Here in the west, preoccupied as we are with health and wellbeing – fretting over the ‘right’ food, exercise, stress and sleep patterns – we were forced to push our indulgences aside, and worry only about the fundamental premise of avoiding highly contagious viral microbes. It was a disorienting experience, to say the least.

Of plague and portraits

by Corinna Cullen, 18 May 2020

Era-defining selfies

Amidst the panicked immediacy of those first moments it was possible to sense that, in the months and years from now, Instagram images of Gwyneth Paltrow wearing a chic black face mask or Naomi Campbell in a hazmat suit at LA airport would become instant signifiers of this time. Seeing the rich and famous dimming their splendour by several thousand lumens provoked two reactions: it seemed to mock those actually on the front line of this health catastrophe, yet also oddly underscored the seriousness of the situation.

Paltrow, a ‘wellness warrior’, is routinely criticised for promoting controversial health treatments, but the advice posted with her PPE Instagram selfie in late February 2020 was sound: ‘Don’t shake hands. Wash your hands frequently.’ If the goddess of health and wellbeing could be affected, was anyone safe?

The portraits of those affected by pandemics, accidental or otherwise, end up defining that era. When we see these images again in the future we will immediately recall this sensation – a gradual and then sickening rush of realisation. This unknowable calamity really was going to affect us, even here on our isolated island continent. It was coming soon, and then it was here … now. We will recall how quickly our lives retracted to the immediate vicinity of our homes and our neighbourhood triumvirates of supermarket/nature reserve/bottle-o/repeat. What, then, of other times and images?

The healthy masked

The masks worn by 17th-century plague doctors are truly the stuff of nightmares. These were for protection, but also imbued with elements of faith and superstition. Stuffed with a compound of herbs to cleanse the air before it reached the doctor’s face, the unmistakeable beak was a threatening identifier of a person with knowledge and health, as opposed to one without. A contrast exists today between those wearing masks in public and those without, since doubt remains about the efficacy of wearing masks to undertake normal activity. The official Australian Government health recommendation is that masks only need be worn by those infected or in direct contact with a person afflicted by the coronavirus. To don one is to declare your belief that this is the right precaution to take, or that you must for your own health-related reasons. In either case, a societal tension is created between those with masks and those without.

Pepys’ personal plague

As Australians wait anxiously to hear when our favourite pubs and restaurants might open again, striking parallels abound: this is obviously not the first time that lifestyle and livelihood have been altered by a pandemic, with familiar neighbourhood spaces shuttered and dark. In an entry from September 1665, London diarist Samuel Pepys (who avoided contracting the plague) compiles an aggrieved tally of the disease’s hold on his city, noting that not one but two of his local watering holes have closed:

‘To see a person sick of the sores, carried close by me by Gracechurch in a hackney coach. My finding the Angell Tavern, at the lower end of Tower Hill, shut up, and more than that, the alehouse at the Tower stairs, and more than that, the person was then dying of the plague when I was last there.’

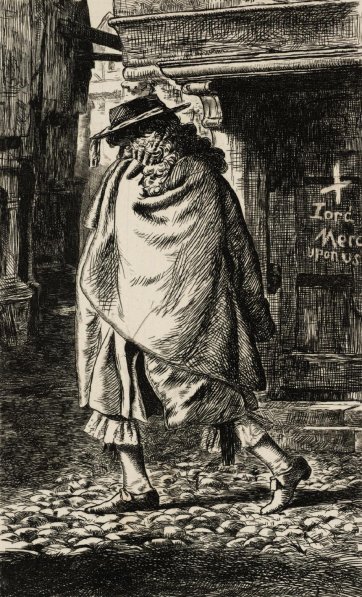

Charles Keene’s Scene of the Plague in London 1665 perfectly evokes Pepys’ experience. The work’s well-to-do gentleman, bewigged and ruffled, delicately holds his cloak across his face as he passes a plague-struck house bearing the legend ‘Lord have mercy upon us.’ It’s a clarion example of the elite brushing up against the reality of the many.

Plague propagandised

Just as much a public relations exercise as the Paltrow insta-selfie, Antoine Jean-Gros’ 1804 epic Napoleon Bonaparte visiting the plague-stricken at Jaffa is an enormous five by seven metres. Viewing this painting in person at the Louvre must constitute the exact opposite experience to the intimacy of scrolling past a casual selfie transmitted via a burbling social media feed. Commissioned by Napoleon to dispel rumours that he had ordered the poisoning of his own infected troops, everything about the work is grand. Reaching out to touch the armpit bubo of a plague-ridden soldier, a god-like Bonaparte demonstrates his divine immunity. Meanwhile, the soldiers’ distress is romanticised, their forms glorified and perfect amidst their torment: one kneels Christ-like at the feet of the soon-to-be emperor.

Pandemic portraiture meets iconography

Other era-defining portraits of people in the grip of a pandemic bear heavy religious overtones, and powerfully, viscerally affect viewers. William Yang’s wrenching documentation of his friend Allan suffering and succumbing to HIV/AIDS comes to mind, as does the famous portrait by Therese Frare of American AIDS activist David Kirby on his deathbed, published in LIFE magazine in 1990. Both of these photographs are composed such that the young man at the centre recalls Jesus Christ, eyes cast up, abandoned to his suffering. This nod to Christian iconography was not lost on viewers: AIDS remains a stigmatised disease, inextricably linked in historical social consciousness to society’s ‘dis-ease’ with homosexuality and gender fluidity.

The composition of these images in turn draw parallels with the macabre and vivid artworks of the various plague epidemics that decimated populations in waves across the last thousand years. Two women lying dead in a London street during the great plague of 1665, one with a child who is still alive (after Robert Pollard) exemplifies this. Here is the Christ-like figure, a fence post standing in as a cross, a cart full of bodies, and the horror of the orphaned babe still feeding. The suffering in these images is real, immediate and inescapable. There is a vast distance between present day images of mask-clad loners haunting empty city centres, and the bodies piling up on the streets in 1665. These days we take so much of the organic messiness of life and death offsite (birth, ageing, terminal illness, death – even war is fought with drones) that we have developed an inability to look directly.

Suffering out of sight

The COVID-19 pandemic has left us with a thousand images of hidden suffering: behind face masks, behind pixellated screens, inside repurposed refrigerated trucks, beneath hazmat suits, and under white sheets on gurneys. Surely the most painful irony of this tragedy is that loved ones are unable to physically be with their family at the moment of bereavement. There is also the creeping dread of learning the reality of the pandemic’s toll on developing countries, hidden from us by geography, isolation and ethnocentric mainstream news. When will we see greater dissemination of images from non-western countries without the resources to carry out social distancing? How will we respond?

Sheltering in place, the majority of Australians have had the luxury of becoming a little bored, perhaps. Maybe we’ve been drowning under the weight of home schooling and/or working from home. Perhaps we’ve never spent this much uninterrupted time with our immediate families! These are all valid experiences, and I am grateful to count them among mine, but an undertow exists – the feeling that something momentous has been occurring elsewhere, and occurring ‘right now’.

The continuing emergence of an extensive array of images – portraits of this time – will complete the picture for us all.

Related information

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!

Plan your visit

Information on location, accessibility and amenities.