I was delighted to be one of this year’s judges for the National Photographic Portrait Prize, colloquially known as the ‘N-triple-P’. It was a rare but welcome opportunity for me to sit quietly and devote myself to looking closely at over two thousand five hundred photographs. As a photographer myself, I love nothing more than seeing what other people are creating with their cameras.

Focussing in on images and making a final selection required deep concentration and robust discussion, and became a most pleasurable experience due to working alongside two fabulous like-minded people: artist Naomi Hobson, from Coen in far North Queensland, and National Portrait Gallery curator Penelope Grist.

The process ran smoothly thanks to the in-house expertise of the NPG team, who enabled us easy access to the images and statements so we could concentrate on our job of assessing them. Interestingly, after arriving at a group of seven hundred images – comprised of photographs that at least one of us picked to be in the initial shortlist – we realised not a single one of them had been selected by all three of us! This meant we had to then look at each of these images together to reach a verdict on the 47 finalists who now feature in the NPPP 2020 exhibition. We had many in-depth discussions and got to know each other quite quickly, as the presence of each image in the final exhibition must be agreed on unanimously amongst the judges. It was a mixture of exhaustive, exhausting and exhilarating.

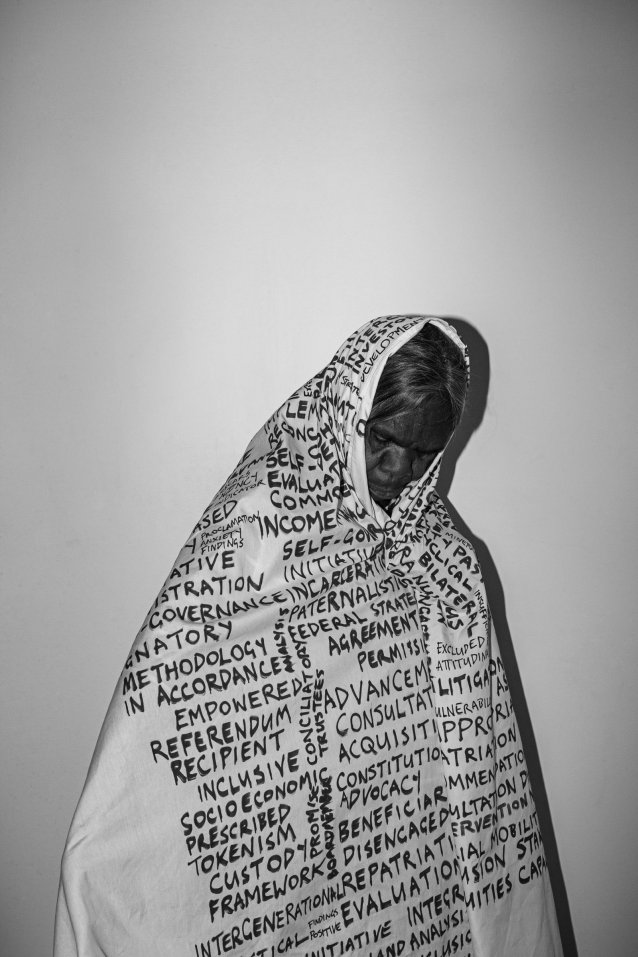

Current themes of everyday life across the country began to emerge as we considered the multitude of photographs. Images of ecological degradation, drought and fire prevailed, as opposed to picturesque landscapes – which of course reflects the recent situation in Australia. There were representations of family bonds, people in hats, people with their beloved pets, subjects with prized possessions, images that shared historical information, and images of hope and of despair. Techniques employed included digital, film, tin-types, colour, black and white and toned images. Some images were straightforward portraiture; others were surreal; some were clever, original ideas; while others were more derivative.