After it was established by legislation at Westminster in 1824 (193 years ago) the site chosen for the new National Gallery was Trafalgar Square, because you could drive there from Chelsea, Mayfair or St Marylebone, but it was also within easy walking distance for many far less affluent Londoners who lived not far east of there. Upon arriving, visitors would enter the National Gallery on an absolutely equal footing, free of charge, and experience there, each in his or her own way, the transformative power of great works of art.

That principle of equity of access has ever since been a noble aspiration for all public art museums, as it is for us here at the National Portrait Gallery. Art is for everybody. In our case, we strive to tell the story of modern Australia through portraits of notable individuals who collectively reflect the shared life and achievements of the whole country, in all our diversity. Many of the subjects of portraits in the collection have lived, or are now living, with dementia. A steadily increasing number of our visitors live with dementia too, and, together with our colleagues at the National Gallery of Australia, we already deliver programs that specifically cater to some of the needs of people who are living with dementia, their carers and companions.

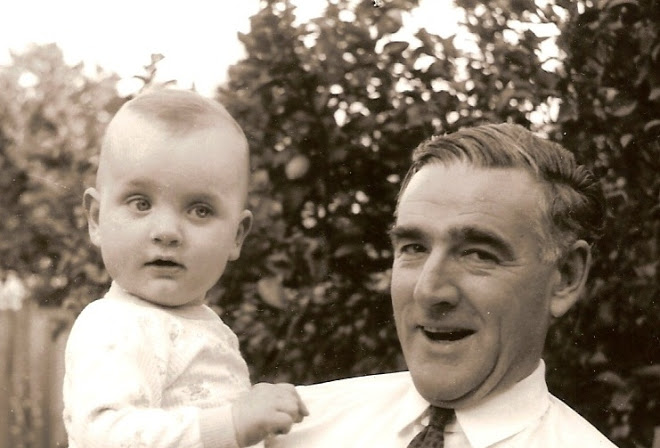

My staff and I receive training in the awareness of dementia. Indeed the whole subject is of personal importance to me because my father, the late Peter Trumble, also lived with dementia for many years, so I know from experience the many ways in which dementia places considerable demands upon individuals, couples, families, friendships, workplaces, and indeed the community as a whole. It is a privilege therefore for us to be able to offer at least some support, mindful that, although necessarily brief, those interactions are perhaps the more important because they exist at all, and are now wholly unexceptional.

Everybody sees things differently. Works of art appeal to us in different measure. They change in the light of circumstance, experience, the passing of years. They can be shaped or distorted by preconception, lapses of memory, strong feelings, or none at all. They vary in the intensity and range of the responses they elicit. They can baffle, disturb, and raise unanswerable questions, just as much as they can delight, uplift and stimulate joy. So, in these respects, works of art teach those of us who are not yet living with dementia that we share with those who are a good deal more in the complex realms of perception, and of vision and of thought, than we often think we do. And that is surely a valuable and humbling insight.