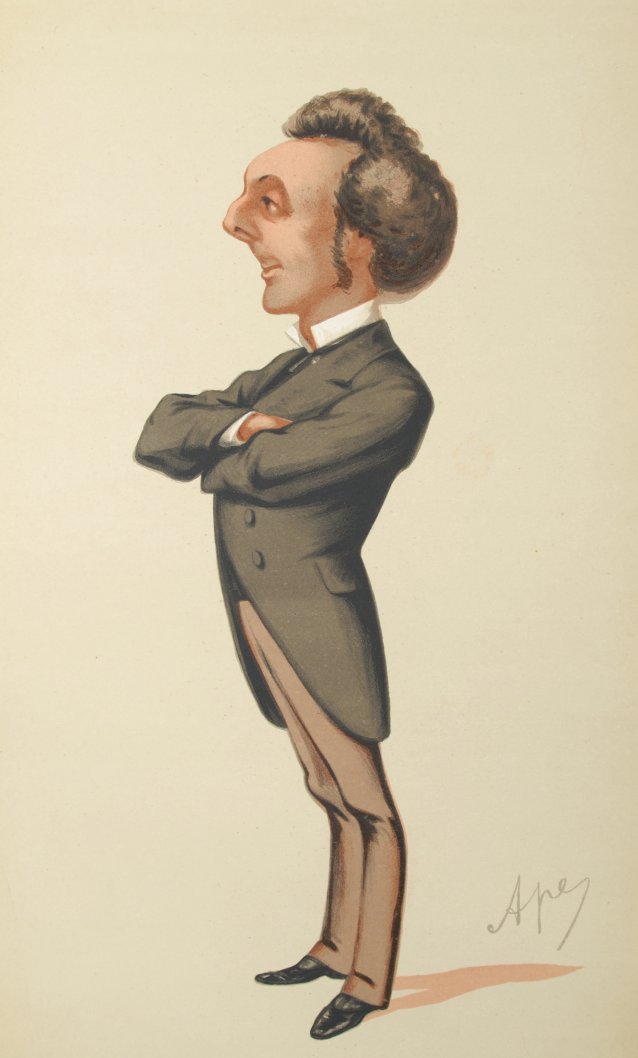

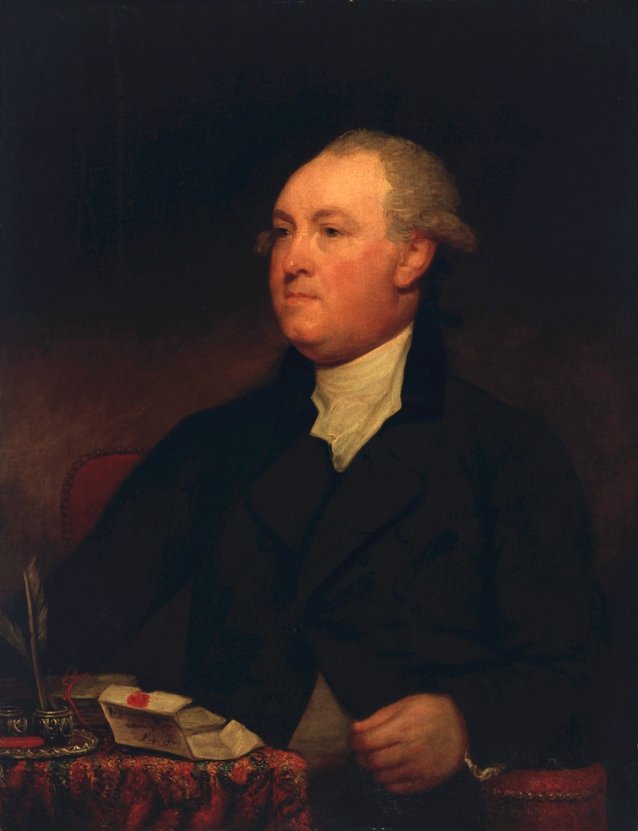

I have just finished reading Victoria Glendinning’s excellent recent biography, Raffles and the Golden Opportunity (2012). By a strange coincidence, having lately read James Pope-Hennessy’s Verandah (1964), I was struck by how very alike the two subjects were, though separated by fifty years (as are their respective biographies): Sir Stamford Raffles and Sir John Pope-Hennessy were both self-made (if largely thanks to other, more powerful people’s patronage). They were limitlessly ambitious for themselves and the colonies temporarily placed under their authority (which was more or less total); inclined to act first and seek permission long afterwards (if at all); much given to hopeless quarrels with subordinates and very good at making every other sort of enemy; passionate about liberal causes; enlightened in respect of local languages, ethnicities and customs; careless with public money (and their own), and prone to elicit strong censure from Whitehall — but to prosper despite that. Pope-Hennessy once said that of the Three Grand Qualifications to Success “the first is audacity, the second is audacity, and the third is audacity.” Though expressing it differently, I am sure Raffles would have agreed. Unlike Pope-Hennessy, however, Raffles created something out of absolutely nothing: Singapore, and, as a free port, having narrowly escaped being shut down thanks to energetic Dutch diplomacy in the early 1820s, in due course Singapore succeeded exactly as Raffles predicted it would. By the time he was my age, Sir Stamford Raffles had been dead for seven and a half years; barely three and a half remained for Sir John Pope-Hennessy.

Audacity, audacity, audacity

by Angus Trumble, 2 March 2017

The biggest difference between the two is that throughout his career Raffles was an employee of that creaking giant the so-called Honourable East India Company, and duly reported to its “supreme government,” i.e. the Company’s Governor-General in Calcutta, who in turn took their instructions from the Court of Directors in Leadenhall Street. Parliament sought to regulate the company through a Board of Control, but the relationship was fractious. In other words Raffles was in private enterprise. By contrast Pope-Hennessy was a public official directly accountable to H.M. Secretary of State for the Colonies. This is of relevance to the history of Australia. In 1788, British colonial possessions other than those of the East India Company were administered by the Home Office — hence the name of Sydney, Lord Sydney having been Home Secretary when the First Fleet arrived here in 1788.

As well, in the 1790s New Holland obviously more directly concerned the Admiralty than the Home Office. The old colonial office (largely for the American colonies) had been abolished in 1782. In 1801 the leftovers — British North America, Newfoundland, the Cape of Good Hope, certain Caribbean islands, New Holland, Gibraltar, St. Helena, Bermuda), most of which were growing in importance — all these were shunted to the War Office. Thenceforth this became the “War and Colonial Office,” nevertheless with far stronger emphasis upon war. Hence the name of Hobart, Lord Hobart (the future fourth Earl of Buckinghamshire) having been Secretary of State for War when in August 1803 a settlement was established on the Derwent River in Van Diemen’s Land.

There was no permanent under-secretary for the colonies (and/or a colonial department within the War Office) until 1825. And it was not until 1854 that the Colonial Office assumed the form in which it is now best remembered, albeit on a miniature scale, its minister being among the most junior in Cabinet — right down there with the Paymaster-General. From the beginning, this Colonial Office’s overriding concern was how to make the colonies look after, defend and pay for themselves. No wonder the Australian colonies developed in such comparative isolation from Whitehall, and with really minimal direction or control. What is so interesting is that the East India Company never saw any commercial potential in New South Wales, despite John Macarthur’s successful introduction of merino sheep in 1796, for example. Nor does the successful establishment of Singapore seem to have done anything at all to alter their view.

You could argue that the central episode of Sir Stamford Raffles’s life was having been for several years the British Governor of Java. When in 1811 Napoleon invaded the Netherlands the Dutch government in exile persuaded the British to occupy their colonial possessions so as to prevent the French from doing so. The understanding was that these colonies would be restored to Holland once the French were defeated. The Dutch knew that if the French took control of their colonies and the British in due course ejected the French, the British would hold onto these territories for themselves, as they did in the Caribbean, Mauritius, the Cape of Good Hope, and elsewhere. So entering into a formal arrangement with the British, confirmed by treaty in 1814, for the time being saved the Dutch their valuable colonial possessions in Southeast Asia. In the interim, however, this is how Raffles was appointed by Lord Minto to be Governor of Java from 1811 to 1815, at which point the island reverted to Dutch control. Raffles argued energetically that the British should hold onto the island, but in a rare instance of containment Whitehall prevailed over him. The cession of Singapore by the cash-strapped Sultan of Johor, another piece of Raffles’s private enterprise, was in due course a completely unexpected bonus. At this point Raffles sailed home to England on extended leave. In a delicious coda, as symmetrical as it is dramatic, on the last leg of his voyage back to England Raffles’s ship called at the mid-Atlantic island colony of St. Helena. There, in the garden of Longwood House, Raffles was formally introduced to Britain’s most famous prisoner-of-war, none other than the Emperor Napoleon himself. They were approximately the same height.

Related information

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!

Plan your visit

Information on location, accessibility and amenities.