Sir Thomas Brisbane’s arrival in New South Wales in late 1821 was met with the usual degree of pomp and fawning. The Sydney Gazette reported, for example, on the nineteen gun salute that greeted the coming to anchor on 7 November of the ship on which he and his retinue had sailed to Sydney, and on the large number of plebs who congregated at Government House the next day ‘to catch a glimpse of our future GOVERNOR’. The day of Brisbane’s swearing-in was marked with further firing of multiple guns and declared a public holiday, with the outgoing governor, Lachlan Macquarie, congratulating colonists for their luck in scoring as his successor ‘an officer of such distinguished reputation and highly established character’.

By the time of his being anointed as New South Wales’s sixth governor – a job he had secured on the recommendation of his friend the Duke of Wellington – Brisbane had indeed distinguished himself through his military service in England, Ireland, Canada, the West Indies, and on the Continent. It has been suggested, however, that Brisbane’s interest in the New South Wales governorship was as attributable to his passion for astronomy as to the desirability of the position as a prestigious career move and the rightful reward for his duty and talents.

Brisbane had been studying the stars since 1798, a close shave with shipwreck that year having prompted him to cultivate a thorough understanding of navigation. In 1808, he built an observatory – one of the first in Scotland – at the Brisbane family’s ancestral home in Ayrshire, where he made observations daily at first light. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1810; later, during the Peninsular War, he created at Wellington’s request a table for determining time by the stars for use by the British army. It’s unsurprising, then, that Brisbane was intent on maintaining and advancing his scientific studies during his tenure as Governor of New South Wales. Consequently, at his own expense, he brought with him to Sydney his personal scientific library along with telescopes and other astronomical instruments, as well as two assistant astronomers, Carl Rümker and James Dunlop.

Like Macquarie, Brisbane chose not to reside primarily at the vice-regal residence overlooking Sydney Cove, opting instead for Government House at Parramatta, the less hectic environment of which presented fewer distractions and hence greater opportunity for astronomical pursuits. Brisbane thereafter conducted observations which constituted some of the most important studies of the southern hemisphere skies made to that date, building a two-domed observatory in the grounds of Government House in 1822. During that year, Brisbane and his team reviewed the catalogue of some 10,000 stars identified by the eighteenth-century French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, and predicted the return of Encke’s Comet.

The Parramatta observatory is held to represent the beginning of permanent scientific activity in Australia, and both Brisbane and his assistants later received medals and other honours for their work, including the Gold Medal of the Astronomical Society (in 1828). Their discoveries were published in 1835 as A catalogue of 7,385 stars, chiefly in the southern hemisphere, prepared from observations made 1822–6 at the observatory at Parramatta.

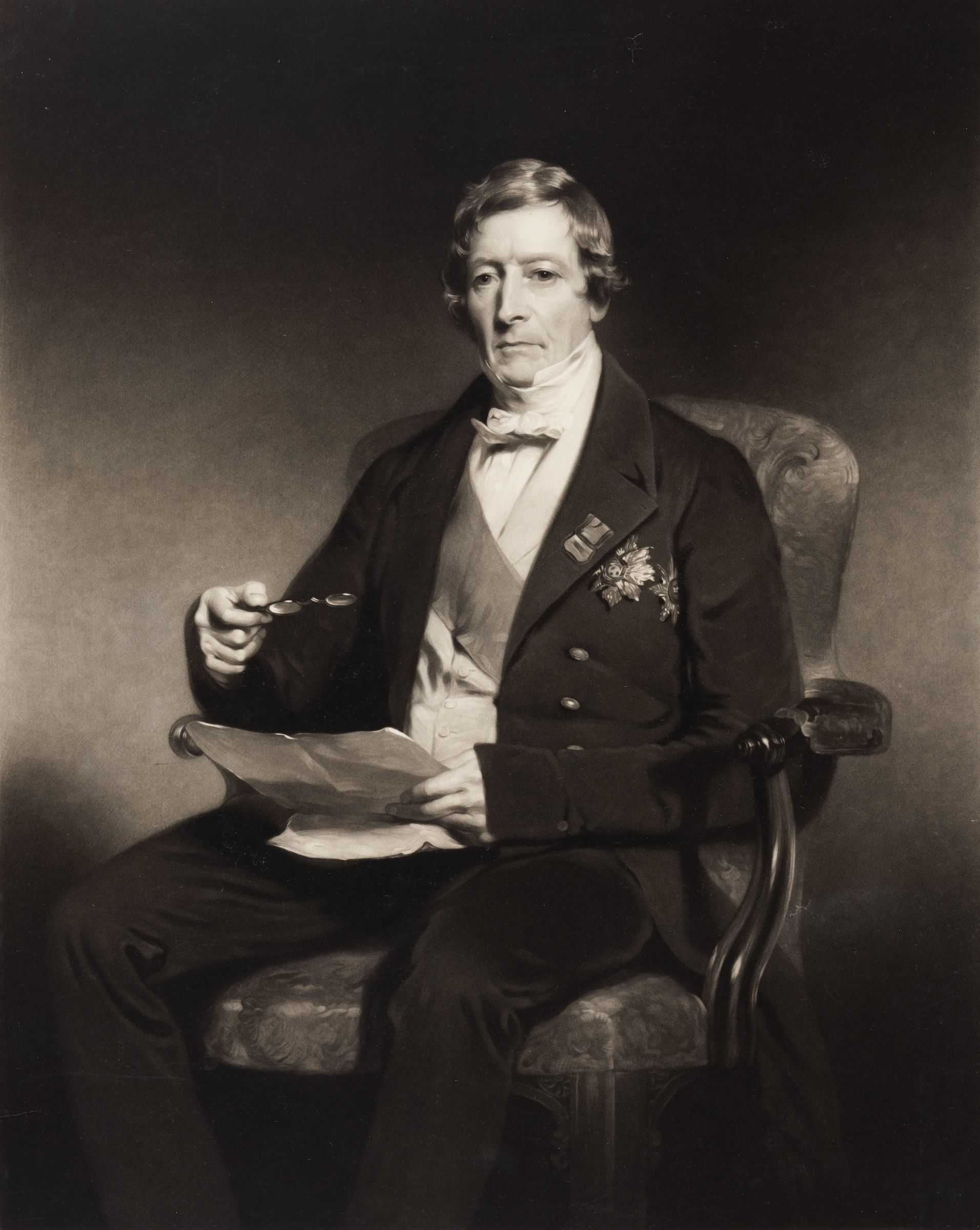

At the conclusion of his term of office, in late 1825, the colony’s leading civil servants sought Brisbane’s permission to commission his portrait ‘as a memento of the warmth and affectionate feelings with which your Excellency’s character has inspired us.’ The resultant painting, completed by the artist and adventurer Augustus Earle in early 1826, was envisaged as ‘a monument of the progress of the fine arts under His Excellency’s administration’, but pointed also to Brisbane’s accomplishments as an astronomer and the ‘founder of Australian science.’

Back in Scotland, he continued his scientific work, establishing another observatory, at Makerstoun, in 1826, and succeeding Sir Walter Scott as President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1833. This appointment was celebrated in 1848 with the commissioning of another portrait from the leading Scottish painter, Sir John Watson Gordon. Wishing to remain associated with the advancement of science in the colony, Brisbane left his collection of instruments at the observatory at Parramatta. They now belong to Sydney’s Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences; the building in which they were once housed, however, exists only as an archaeological site, Brisbane’s observatory having been demolished in the 1850s.