James McCabe provides proof that hanging wasn't necessarily a fate reserved for the perpetrators of murder and other deeds of darkest hue. A Dubliner, McCabe had been transported to New South Wales for seven years in 1817 and then banished to the penal station at Port Macquarie in June 1822. Recaptured after absconding, in 1824 he was sent to Van Diemen’s Land so that he might serve out the rest of his sentence at Macquarie Harbour, the remote west coast shipbuilding and timber-getting settlement reserved for those considered the most intractable and irretrievable offenders. Later that year, he and several others escaped in a stolen boat under the leadership of the soon-to-be infamous brigand, Matthew Brady, with whom McCabe had become acquainted in New South Wales.

McCabe was listed among the convicts who had 'absented themselves from their usual Place of Residence' in early 1825 but was later expelled from Brady’s gang, thereafter going it alone in thievery and knavery in the northern and midlands districts of the island. He was eventually apprehended near Bagdad having bailed up a man on the King’s Highway and stolen his clothes, money, watch and horse.

Tried in early November 1825, McCabe was sentenced to death for robbery. This judgment was brought into effect on 6 January 1826, McCabe being among the eight thieves despatched in a mass hanging in the yard of the Hobart Gaol that morning.

The Colonial Times provided a blow-by-blow account of the proceedings, from the unfortunates being marched into the yard, pinioned, and positioned above the drop, to the reading of 'the solemn service of the dead, in a tone of equal feeling and impression' by the Reverend William Bedford. 'At this moment, the scene was awful beyond description', the paper said. 'To witness eight fellow-creatures in the prime of life, about to be removed from this world by a violent death... is a spectacle which we trust will not be without its effect upon the crowd who witnessed it.' McCabe was the last to ascend the scaffold and was reportedly 'firm and resigned' in doing so. 'He did not betray the smallest fear of death, while he fully acknowledged the justice of his fate. Indeed the whole of the eight exhibited a firmness and composure which nothing but the consolations of religion could produce.'

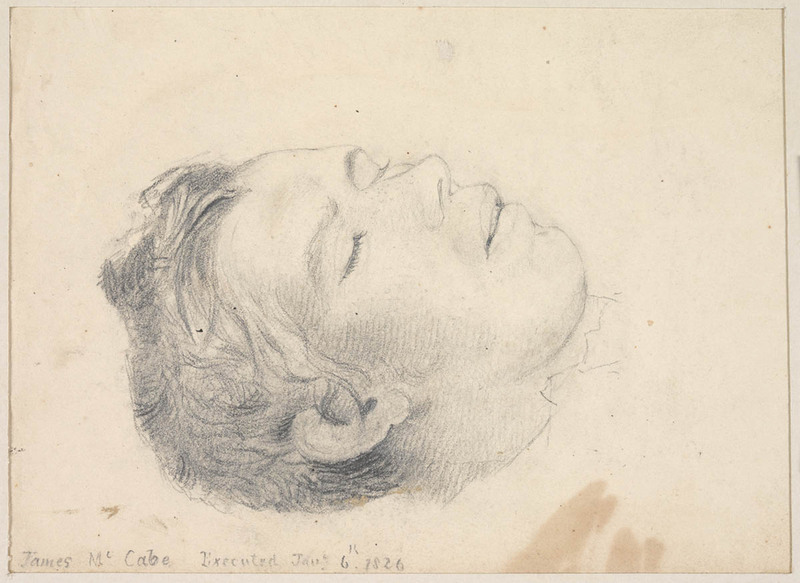

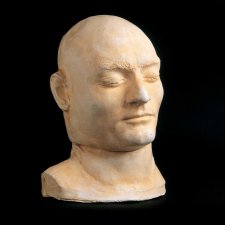

Convict and artist Thomas Bock had made a sketch of James McCabe during his trial a few months previously and subsequently issued a lithographed version of the drawing. Bock was also on hand to make a portrait of McCabe as he lay on the slab in the gaol deadhouse, such likenesses supposedly supplying proof - to gentleman of certain 'scientific' persuasions - as to why the dead man had transgressed in the first place.