Beyond the centenary of the ANZAC landings at Gallipoli which we observed last 25 April, a number of other notable anniversaries converge this year: the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo (18 June); the tercentenary of the death of King Louis XIV (1 September); the six hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt (25 October), and the eight hundredth of Magna Carta (15 June). It is a matter of considerable debate exactly where in Australian constitutional and legal arrangements the influence of Magna Carta may still be detected. Agincourt is likewise a dim memory, mostly filtered through the text of Shakespeare’s Henry V, and nowadays the Sun King shines less brightly than perhaps was once the case.

Waterloo, however, deserves a little focussed consideration, for in the decades following 1815 numerous Waterloo and Peninsular War veterans came to Australia, most notably Governors Sir Charles Augustus FitzRoy of New South Wales and Lieut.-Col. George Gawler of South Australia. For many years the memory of those campaigns formed a kind of supplementary glue in colonial society—particularly for middling officials such as Major William Irwin, of the 28th Regiment of Foot, who was wounded at Quatre Bras and died at Parramatta in 1840, aged 56, and his comrade the Anglo-Irishman James Henry Crummer, who likewise distinguished himself at Quatre Bras and at Waterloo; arrived in Sydney with the same regiment twenty years later, in October 1835, and served as justice of the peace, police magistrate, and commander of the iron gang at Newcastle.

Another Anglo-Irishman, Francis Allman (1780-1860), meanwhile, who with his Regiment (the 48th) arrived in New South Wales in 1820, was posted as captain to the penal settlement at Port Macquarie, then to Newcastle, Wollongong, Campbelltown and finally as police magistrate to Yass, where he is buried. There are many other examples. Between them it is to me especially affecting to imagine eyewitness accounts of varying degrees of accuracy and embellishment, dealing with the deeds of Wellington, Picton, Uxbridge, and Blücher, for example; the attack upon Hougoumont; the charge of the Scots Greys, or the storming of La Haye Sainte—told and re-told in sweltering mess rooms and parlours, on verandahs and in smoky taverns with, in the background, the raucous squawking of sulphur crested cockatoos, the laughter of kookaburras, and the drone of blow flies and mosquitoes.

As far as we know only one soldier who fought in the Battle of Waterloo was born in Australia, but that there were any at all is simply incredible. This was Andrew Douglas White, a young and inexperienced staff lieutenant in the Royal Engineers, who was born at Sydney Cove in September 1793, the son of John White (1756-1832), naval surgeon on the first fleet, and his convict housekeeper and concubine (to use the term favoured by the Rev. Samuel Marsden), Rachel Turner (1762-1838).

Another of Dr. White’s assigned convicts was the artist Thomas Watling, and it is now thought that numerous drawings once ascribed to Watling were in fact executed by White himself (including a batch in the British Museum)—but that is quite another story.

Dr. White’s tour of duty at Port Jackson was very hard indeed, for to him fell part of the responsibility of treating the hordes of sick and dying who arrived at Port Jackson in June 1890 aboard the notorious second fleet. Despite having been given several advantageous grants of land, Dr. White was ground down by his six years in New South Wales, and at length applied for leave to go home to England. He departed at the end of 1794, leaving Rachel Turner and the baby behind. Several years later Dr. White sent for the boy and had him brought to England. He was entrusted to the care of the sister of one of his naval cronies, who evidently, much later in 1812, arranged for Andrew Douglas White to join the army. Andrew White served on the staff of General Graham at Waterloo, and returned to Australia nearly ten years later in 1822, to take up his father’s property and become acquainted with the mother from whom he had been separated at the age of only eighteen months.

By this time his mother had evolved from Rachel Turner into Mrs. Thomas Moore, and lived in prosperous and eminently respectable retirement at Moorebank, a handsome tract of land near Liverpool, New South Wales—thoroughly cleansed of the stain of penal servitude. Her son predeceased her (at Parramatta), and she is said to have treasured his Waterloo medal until she too died about a year later in 1838, aged 76. Mr. and Mrs. Moore had no children of their own, so in 1840 Thomas Moore left his whole fortune to the Church of England for the establishment of what eventually became Moore Theological College, and St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Sydney.

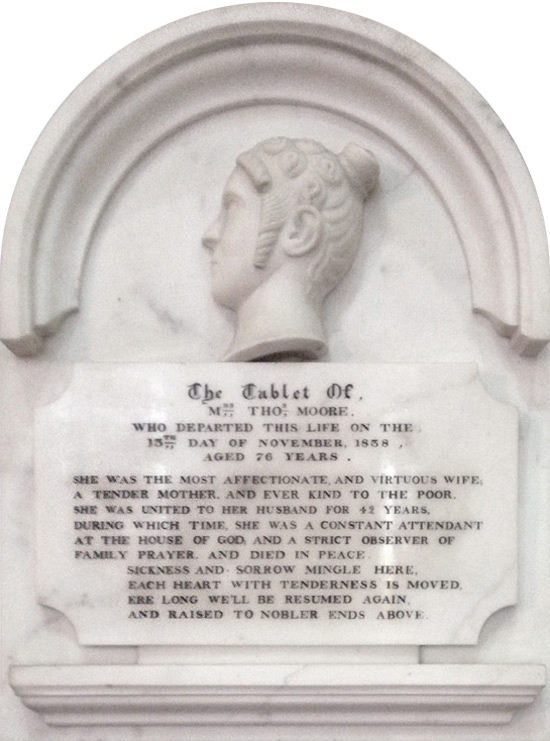

A fine marble wall monument to Mrs. Moore in St. Luke’s Church, Liverpool, was executed on Mr. Moore’s instructions in 1839 in the manufactory of Mrs. Ann Clewett in Pitt Street, Sydney. That tablet is a remarkable rarity for it carries her bas-relief profile portrait, stiff and pastry-ish, certainly, but dignified, alert, even spry. She wears her hair in the mode suddenly brought into vogue upon the accession of Queen Victoria barely two years prior. Indeed Mrs. Moore’s tablet is one of only a handful of works of art that are readily identifiable with Mrs. Clewett’s workshop, and the portrait one of the earliest portrait sculptures to have been carved in New South Wales. As the Sydney Herald remarked in 1839, it “speaks highly of the ability of her workmen”, who were almost certainly themselves assigned convicts. Alas we do not yet know who they were.

The elegant inscription on the monument reads: “She [Mrs. Moore] was the most affectionate, and virtuous wife, a tender mother, and ever kind to the poor. She was united to her husband for 42 years, during which time, she was a constant attendant at the house of God, and a strict observer of family prayer, and died in peace…” Whether or not Mrs. Moore’s charitable and religious activities were primarily intended either by herself or her husband (or both) to be expiatory—it seems likely—at the same time, in the absence of any legitimate progeny, those three key references, namely “tender mother,” “kind to the poor” and “family prayer,” must have recalled to anyone who knew Mrs. Moore even only slightly the hard facts of her early life—facts that in the 1830s in New South Wales she had in common with a high proportion of even the most respectable female ex-convicts.

Rachel Turner was tried and convicted at the Middlesex assizes on December 12, 1787, aged 25. She was sentenced to seven years’ transportation, and was consigned to the infamous ship Lady Juliana, which sailed from Plymouth on July 29, 1789, carrying 226 female convicts, the vast majority of whom were London prostitutes. Lady Juliana took 309 days to reach Port Jackson, one of the slowest voyages on record, largely because of extended stops at Tenerife, Cape Verde (Santiago), Rio de Janeiro (45 days) and the Cape of Good Hope (nineteen), during each of which the corrupt officers and crew made the women available on a commercial basis to hundreds, possibly thousands of men in total. The Lady Juliana had every reason to have become widely known as “the floating brothel.” In any case, the ship’s steward John Nicol recalled, “when we were fairly out to sea, every man on board took a wife from among the convicts, they nothing loath.” Though all surviving accounts are partisan and hostile, the women on board were said to be idle, noisy, unruly, fond of liquor, and therefore prone to fighting amongst themselves. Four women died on the voyage, and, incredibly, only one infant was born en route. 222 women convicts, including the baby, duly arrived at Port Jackson on June 6, 1790, just when food shortages were at their most critical. This was the formative experience of Rachel Turner, the future Mrs. Moore.

No doubt she was fortunate in having being assigned at first to Dr. White, and in having been eventually reunited (after nearly thirty years) with their Waterloo veteran son. Though effectively abandoned by the doctor and separated from her child in 1794 (with what must have seemed no conceivable prospect of ever seeing him again), by January 1797 she was married to Thomas Moore—even in these melancholy circumstances another stroke of good fortune, for, as we have seen, Moore soon prospered and eventually made his fortune in land and investments. So the monument Mr. Moore placed to Rachel’s memory in St. Luke’s, Liverpool, forty-two years later, of which they had for decades effectively been the foremost citizens, is fascinating not least because it pointedly refrains from obliterating several explicit but gentle references to her early life. And there is even the strand of maternity that connects the monument and its subject to the famous Battle of Waterloo.