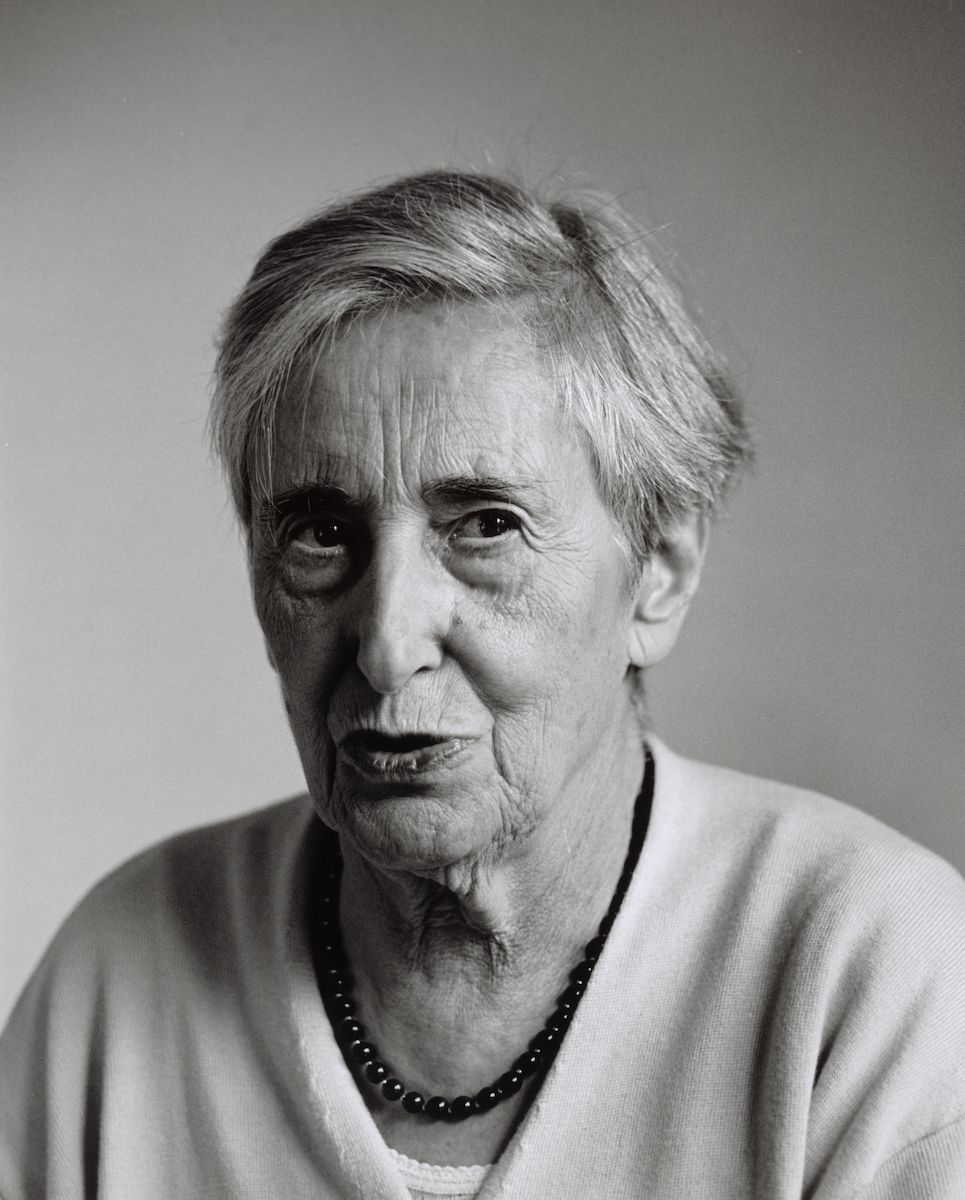

If I did not know the date when Ursula Hoff posed for her portrait photograph by Francis Reiss I could make an accurate guess. It must have been taken shortly after she had her hair cut short in the winter of 1994. For decades Dr. Hoff wore her hair gathered into a rather severe bun. The new “do” was a surprise, and a delightful one, not merely because its softness suited her, but also because it seemed to shave more than a decade off her great age of 85. She fielded the flow of compliments with modesty but unmistakeable and disarming pleasure.

I first knew Dr. Hoff when in 1986, long after retiring from the National Gallery of Victoria, she taught a graduate seminar on Rembrandt. Her doctoral dissertation “Rembrandt and England” had been printed in Hamburg more than fifty years earlier, and was still remembered with reverence at the Institute of Fine Arts in New York after sixty. Her interest in Rembrandt was renewed in the 1980s by pioneering technical and conservation work undertaken for the Rembrandt Research Project, which suggested that each successive generation fashions for itself a bellwether Rembrandt. Dr. Hoff spoke in complete sentences, at times deploying the single raised eyebrow of scepticism to withering effect, but her laughter was musical. (She loved Mozart and hated Wagner.)

Although she published widely on many subjects, including her lifelong friend Arthur Boyd, Dr. Hoff’s monograph on Charles Conder (1960) is my favourite. Its impact continues to be felt, and dedicated Conderistas everywhere rightly salute her prescience, intellect and taste. I want to say that one may detect all three in her portrait, but perhaps this is the game that memory or affection continue to play in the mind of a grateful pupil long after the beloved teacher has died.