Under the Act for the Relief of the Poor (1601), the so-called ‘Old Poor Law’, the situation of the mentally ill or disabled was particularly dire. Some of the afflicted remained in the care of their families, with food, clothing and occasionally nursing assistance subsidised through ‘outdoor relief’. Where such family support was unavailable, parishes provided asylum in the primary institution of public welfare, the workhouse.

As one medical observer noted in the mid-18th century, however, ‘the law has made no particular provision for lunaticks and it must be allowed that the common parish workhouses (the inhabitants of which are mostly aged and infirm people) are very unfit for the Reception of such ungovernable and mischievous persons, who necessarily require separate apartments’. Indeed, with management of parish workhouses being increasingly undertaken by private concerns, some contractors would insist that they be excused responsibility for the ‘raving’ or ‘lunaticks’. This left the parish Overseers of the Poor and the visiting Quarter Sessions magistrates with few options, and the ‘furious’ were often confined with the criminal in a local gaol or house of correction.

An 1807 parliamentary Select Committee on the State of Criminal and Pauper Lunatics found that, of 2,398 pauper lunatics so identified, 1,765 were living in the workhouse, with 113 in a house of correction. This leaves rather more than 20 per cent of the mad poor unaccounted for and unconstrained, living in the community and surviving on parish outdoor relief, perhaps supplemented by odd jobs and begging. Amongst this population we find Dempsey’s Little John of Colchester, A maniac, Whistling Billy and Billy Bean.

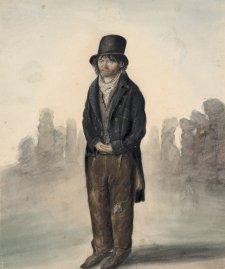

The artist shows considerable sensitivity in his portrayal of the pauper lunatic Little John of Colchester. John’s wrinkled brow and tiny, tightly clasped hands suggest extreme anxiety, while his eyes reveal a disengagement or inwardness. Furthermore, in the background of the work, Dempsey has washed a frieze of wobbly, blurry watercolour verticals that could be distant trees, or standing stones, or human figures in fog, perhaps indicating an intuition that for Little John, the world outside his madness is nothing but a parade of ghosts.

A maniac is not identified. His dark and staring eyes and his determined grip on the sheaf of papers in his hands might imply, however, some obsessive-compulsive disorder, a monomaniac fixation on a perceived legal injustice, perhaps, or it may be that the writing indicates the hypergraphia that is often associated with temporal lobe epilepsy. This work also shows that, for all his occasional gaucheness, Dempsey can be striking and original in his visual metaphors. Behind the figure of the maniac, a wide door opens into inky blackness, into the dark experience of insanity, inhumanity and incarceration.

Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, presented by C. Docker, 1956

30 June 2017

Those of you who are active in social media circles may be aware that through the past week I have unleashed a blitz on Facebook and Instagram in connection with our new winter exhibition Dempsey’s People: A Folio of British Street Portraits, 1824−1844.

Dempsey’s people: a folio of British street portraits 1824–1844 is the first exhibition to showcase the compelling watercolour images of English street people made by the itinerant English painter John Dempsey throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!