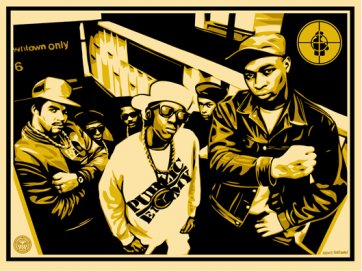

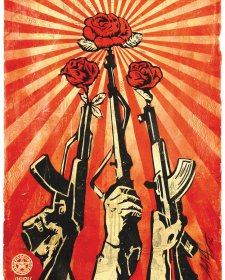

It's not often that an artist is arrested walking into the opening of their first museum retrospective. And considering that this same artist's portrait of the new president was being acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in Washington at the same time, the whole scenario seemed even more unlikely. The artist was Shepard Fairey, catapulted to fame during the 2008 presidential election with his resonant image of Barack Obama, but known primarily for his street art, posters and illustrations. Fairey was apprehended by the police for graffiti offences as he entered the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston where a major exhibition of his work was being held. He had been postering walls of the city with his stickers and posters. Long before his art appeared in galleries, Fairey had populated the streets with his striking designs. Fairey (born 1970) graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1992 but had already begun to be known by his peers for his sticker campaigns that took his images to the street. Fairey has said that he wanted to share his images with an audience and, especially before internet, abandoned buildings, urban spaces and city streets provided high visibility. This visibility has come at a cost: his arrest on 7 February this year for tagging is his 15th such conviction. After he graduated, Fairey set up his own printing business, which eventually expanded to become the design agency Studio Number One, founded in 2003 with his wife Amanda. Fairey designed posters, t-shirts a suite of successful record covers for bands such as the Black Eyed Peas, Anthrax, Smashing Pumpkins and the poster for the film Walk the Line. Fairey's commercial work and his private passions aren't always easy to separate, but generally his posters announce his politics. Wearing his heart on his sleeve, Fairey has made posters of his favourite musicians - Joe Strummer, LL Cool and Tupac Shakur – and his strongly held causes – the environment and the war in Iraq.

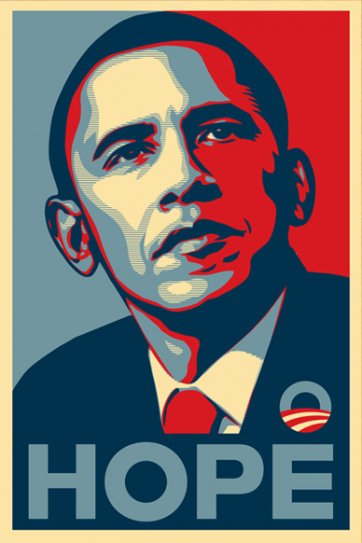

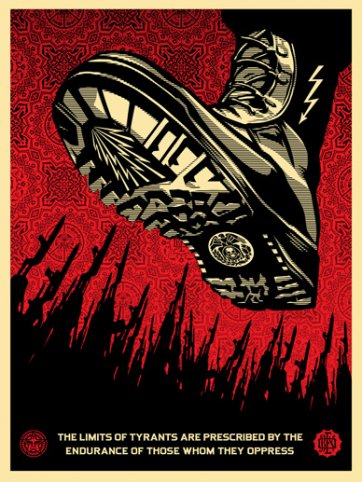

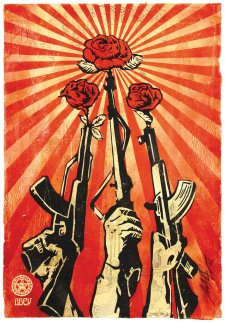

Fairey's posters combine contemporary appeal with a strong retro note, showing a debt to Andy Warhol, to the design of socialist posters created during the 1920s and to South American posters of the fifties. Assimilating these influences, Fairey has produced a body of work characterised by strong graphics and simple but powerful colour combinations intended to compete against the busy distractions of the urban streetscape. While many of his posters carry a strong political message, Fairey has generated numerous portraits. His portrait heads tweak the celebrity cult that Warhol mined but there are fewer movie stars and more musicians, artists and sportsmen. These images of working class heroes and the democratic mode of distribution record a generational shift evident in the series of anti Bush images that were directed against the policies of George Bush and his government. Fairey notes that his posters had usually been directed against something rather than endorsing it until Barack Obama announced his presidential candidacy. On his own initiative, Fairey launched a poster campaign in support of Obama. The striking black red and pale blue image of Obama ‘took off in a viral way that the internet allows these things to take off' and images began to appear on t-shirts, on stickers and on walls all over the United States, quickly becoming the iconic image in the presidential contest. It was inevitable that Obama's campaign managers approached Fairey to secure official endorsement to use the image, its aspirational message and its street cred. Americans of every political stripe responded and the rest is history.

Michael Desmond

Senior Curator

Artist Statement

Iconography is everything. In my art and design career, most of the work I’ve created has revolved around the incorporation of emblematic elements that serve as reference points for certain ideas. Even if it’s just the angle of a pair of eyes or the symmetry of an image, there are ways to communicate very directly through images, just because most people have an innate understanding of the meaning of visual cues.

When I make a portrait, I try to capture the whole person, not just how they look but their iconic essence. Most of the portraits I make are of people I want to celebrate: trailblazers who made an impact on me and the culture I care about. Some of the portraits are cautionary, depicting dictators or authoritarian figures who abused the power that other people vested in them. But either way, I portray people who embraced and fought for particular ideas. Because those people have become known for representing their ideas, I can in turn take those ideas, express them graphically, and use them to represent those people. Then I distill out any superfluous elements as a way to keep the core concept in the forefront, and iconography is born—the person and the ideal become one and the same.

This practice of injecting a person’s image with certain values is also a means to create propaganda, and occasionally I try to comment on that. Some of the portraits I make aren’t even about the person depicted, but about the power of presentation. When you dress something up to look a certain way, people tend to assume it actually is that way, and that’s how they get manipulated.

Coupled with the allure of the portraits is a motivation to get people to think. I want to make them consider how much they believe what they see. I try to enhance my own agenda—to get people to be more suspicious of seemingly friendly corporate or political messages—by incorporating a distinct style, elements and approach to illustration, along with a particular sense of ironic humor. I use certain clues to indicate whether a portrait is an endorsement or not, but I generally try to leave out anything too direct that might point someone toward a particular conclusion if it’s not one they would otherwise reach on their own.

The obvious exception to that rule is the Obama Hope poster. As important as I think it is for people to question everything, it’s equally important for people to stand behind the things they believe in. Because I knew I stood behind Barak Obama one hundred percent, I wanted people who may have never even heard about Obama or his principles to see this portrait of him and immediately see that he was a man of vision, thoughtfulness and idealism. Once enough people had seen it, it became the icon of the campaign. Just as Obama had represented all the qualities I wanted to see in a leader, the portrait came to be a representation of everything that drew people to Obama. In a way, the power of the icon was that it made him iconic.

Shepard Fairey