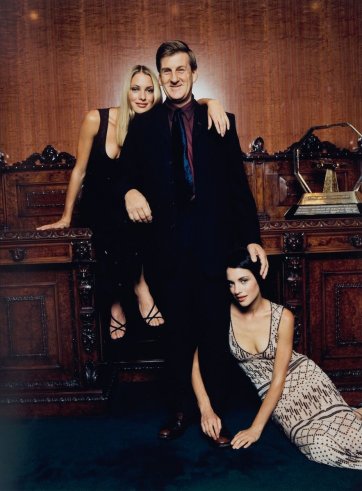

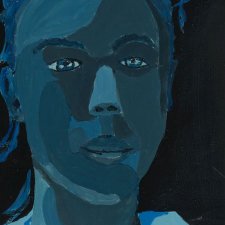

Mirror with a memory: Photographic portraiture in Australia explores both the formal and vernacular traditions of photographic portraiture and promotes a dialogue between the two.

The vernacular encompasses the work of amateur and unknown photographers, while the formal is aligned with the professional and public uses of the photographic medium.

Mirror with a memory highlights the continued power of photographic portraits in peoples' lives against a background of claims for the death of the portrait brought about by digital imaging and the loss of faith in photographic 'truth'.

The exhibition also introduces another way of thinking about photographic portraits, as objects. As such, they have specific physical properties related to scale, process and manner of presentation, and intangible qualities related to history and memory.

Mirror with a memory is arranged in two parts, from the 1840s to the 1920s, and from the 1920s until the present day.

Helen Ennis, Guest curator

Mirror with a memory: Photographic portraiture in Australia continues the National Portrait Gallery's commitment to exhibitions in which photographs are the subject or are a major component.

Portraits displayed in galleries such as Australia's National Portrait Gallery represent but a tiny fraction of the portraits which exist in the community. All over the country there are micro-portrait galleries in virtually every home - to be found between the covers of literally millions of family albums. These, in turn, are but a part of the vast and unimaginably complex reservoir of portraiture across the Western world that has developed since the advent of photography.

Mirror with a memory attempts to suggest some of this huge but largely invisible dimension of photographic portraiture in Australia. The exhibition includes many of the photographs and photographers who have entered the canon of Australian art, yet it also pays particular attention to the personal and the private.

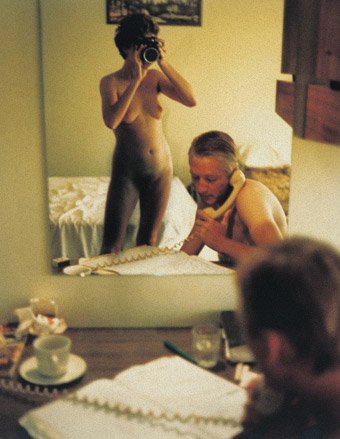

Mirror with a memory is a phrase that aptly describes the earliest form of a widely produced photograph, the daguerreotype; it is also the title of Carol Jerrems' intimate 1976 glimpse of domestic existence. Another dimension of the title is significant - a mirror as object. As such a photograph has a scale and a form and shows the cradling of reverence or the scars of rejection. Photographic portraits have been variously incorporated into an array of decorative arts objects, a number of which are included. Thus photographic portraits can possess that quality of presence that we value so much in portraiture in all its forms.

I am particularly pleased that in mounting Mirror with a memory the National Portrait Gallery has been able to work closely with guest curator Helen Ennis. With great conceptual flair she originated the idea of the exhibition and in curating it she has brought to bear her broad knowledge of Australian photography. Her thought-provoking exhibition will, I am convinced, make an important contribution to our understanding of Australian portrait traditions. I am also grateful to Geoffrey Batchen who has provided a stimulating essay for the catalogue.

Finally I would like to pay tribute to all the lenders to Mirror with a memory; its richness results from the cooperation of many individuals and in particular of our sister institutions who have again embraced a National Portrait Gallery exhibition with enthusiastic support.

Andrew Sayers, Director, National Portrait Gallery