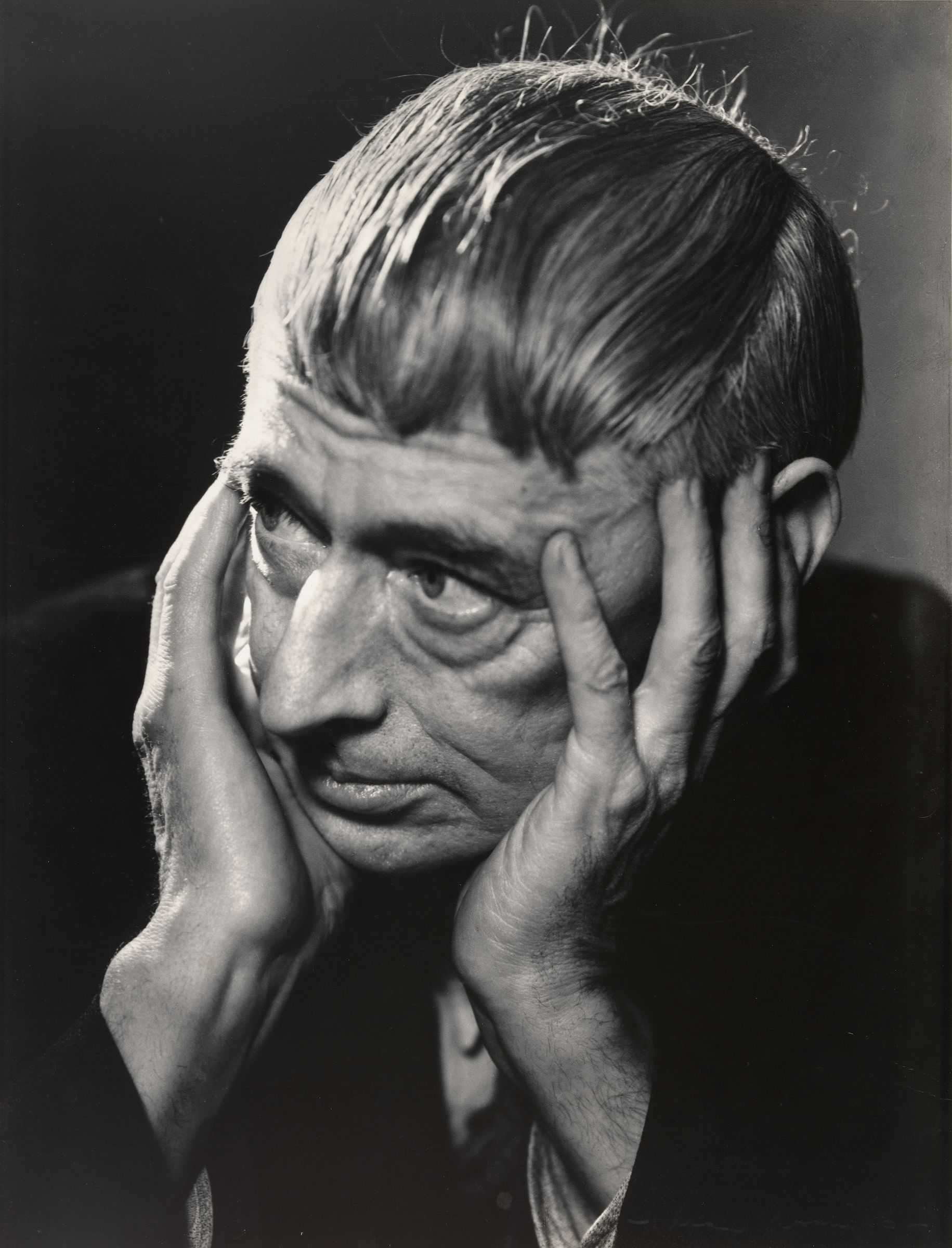

Max Dupain is synonymous with the ascendancy and acceptance of modern photography in Australia. Although he is more widely recognised for his beach scenes and documentary photography, Dupain’s portraits also reflect his bold, stylish approach.

Vintage Max

Max Dupain put his lack of clannishness down to a temperament which inclined to the stoic and an early life as an only child. He relished the solitude of his darkroom, familiar places and routines and the early morning calm of Sydney Harbour where he rowed his scull until curtailed by ill health in the early 1990s. He was not a joiner or follower of teams; he was republican in politics and agnostic. Philosophically, Dupain mixed rationalism with a less defined alliance with the passionate exhortation to live directly in one’s environment, body and heart. This philosophy was espoused by poets and writers such as D.H Lawrence, from the movement known in the 1920s and 1930s as Vitalism.

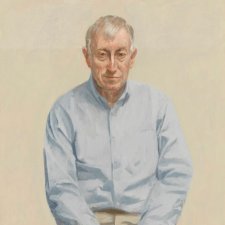

Despite acknowledging he was a bit of a loner by temperament, portraiture was a significant part of Max Dupain’s personal and professional work. He included some dozen or so portraits in his selection for his 1948 monograph, out of fifty plates showing ‘my best work since 1935’. Dupain’s images, including many portraits especially of the 1930s to 1960s, have stamped the public image of this era of rapid progress and increasing cultural sophistication in Australia. Portraiture was at the top strata of Dupain’s first three decades of work but volume decreased markedly from the 1960s when Max Dupain and Associates, his business, began to specialise in architectural and industrial commissions.

As a schoolboy camera enthusiast Dupain’s photography comprised mostly impressionistic romantic landscapes, some unremarkable still life studies and only the occasional portrait of family and friends.

After failing the Leaving Certificate twice, Dupain spent three years from 1930-34 apprenticed to Cecil Bostock, a commercial artist turned photographer in Castlereagh Street, Sydney. When Dupain left to start his own studio in 1934 in a room at 24 Bond Street, he had little experience with commissioned portraiture. He adapted very quickly and was soon patronised by Sydney Ure Smith as the hot, sharp, dramatic, sexy look in modern photography. Ure Smith was the doyen of art and lifestyle publishing. In October 1935 in The Home magazine Ure Smith published Dupain’s review of a 1934 monograph on the surrealist photography of American-born Paris-based artist Man Ray. Two months later a portfolio of surrealist nudes, clean, sharp still-life studies and portraits appeared in Ure Smith’s magazine Art in Australia.

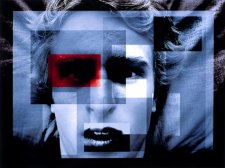

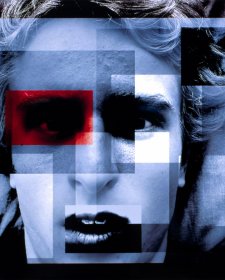

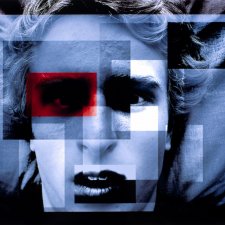

One of Dupain’s earliest (presumably commissioned) portraits was of artist and author Norman Lindsay in 1936. This would have been an honour indeed. Dupain had written letters to Lindsay in 1932 sympathising with the artist’s controversial writings criticising ‘wowser’ constraints on Australian life. Dupain’s portrayal of Lindsay is not of a rebel or effete bohemian; it is cast in the modern photography style with simple lighting. However, Dupain’s late 1930s study of graphic artist Hera Roberts, with her image doubled in a mirror, was modelled closely on Man Ray’s work with a touch of the allure of British society photographer Cecil Beaton.

Other contacts and introductions in these early years led Dupain to d work for the Australian Broadcasting Commission as well as for David Jones department stores. He made many glamorous studio shots of beautiful socialites (including his own cousin Lucille), fashion models and celebrities in the mid to late 1930s with fashionable dramatic top and side lighting known from the movies as ‘Hollywood’ lighting.

Dupain passionately believed in the greatness of traditional art forms, always placing photography a poor second to architecture, music and old master painting. He loved classical music – especially Beethoven – but his taste also included some of the more modern figures such as Debussy. His artists and musicians in action often seem lost in their performances, as in his studies of the Budapest String Quartet photographed during their 1937 visit to Australia. In the late 1930s when the Russian Ballet was in Sydney, Dupain also fell under its spell. He made studies ranging from the introspective mood of Paul Petrov’s head and torso to the zephyr-like, dark-eyed beauty of Toumranova with her matched lacy shawl and curly hair, or the sad reverie of Hélène Kirsova in a sharply angled view which suggests the jerky movement of the doll in Petrouchka.

Dupain’s best portraits of these decades combine a dramatic boldness in composition and lighting, with telling inclusions of foreground or background elements as in the portrait of artist Hal Missingham (also Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales and a fellow photographer), his hand raised in the air eloquently but inexplicably; or in the view of Robert Emerson Curtis drawing a profile of Clem Seale in 1945. Dupain’s portrait of the famed fashion photographer George Hoyningen Huene in Dupain’s studio in 1937, with tie undone and crumpled shirt, has its own, perhaps unintended, seductive aura.

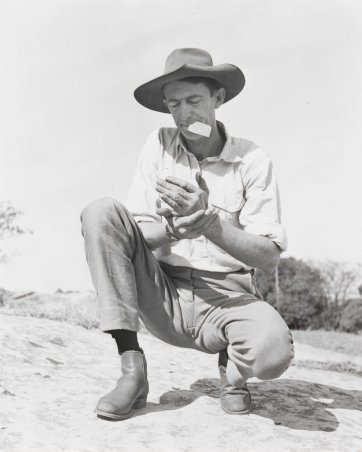

In commenting on his mentor’s portraiture, David Moore observed that there is a marked change after World War II to images with greater spontaneity which seem to seek the decisive moments of reportage. Certainly Dupain’s war time portraits, including those of New Guinea native bearers and those from his last active pursuit of portrait commissions in the 1950s, are powerful and direct. The elderly poet Mary Gilmore is shown in half-light, seemingly in mid sentence, firing with undiminished vitality. In 1954, in the composition of his portrait of the young Harry Seidler and visiting master of modernism Walter Gropius, Dupain leaves a tense space and sense of the historic moment; Dupain would go on to be Seidler’s photographer of choice for the next thirty years. Not all of Dupain’s favourite portraits, though, were of the famous. Among the later works, is the 1957 portrait of model-maker Charlie South, seated simply in his cluttered office and worn clothes. The image recalls Dupain’s earliest documentary images in Sydney of homeless men, victims of the Depression, living in the Domain and parks in Sydney well into the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Few of Dupain’s later portraits truly rival those made before the late 1960s, when he began to specialise in what he called his ‘long suit’ – a love affair with modern architecture. In this author’s experience, Dupain’s ability to work with the environment and the moment were undimmed in the 1980s. He photographed me in 1982 and chose a moment ’between takes‘ when I was idly twisting my ponytail, to render me as glam as Greta Garbo. He transformed me (in daggy overalls in an ugly bedroom with my new baby) into a mysterious Madonna and child. He shot at most two rolls of film in 15 or so minutes; there was no wasted chat or inciting the subject to perform.

Gael Newton