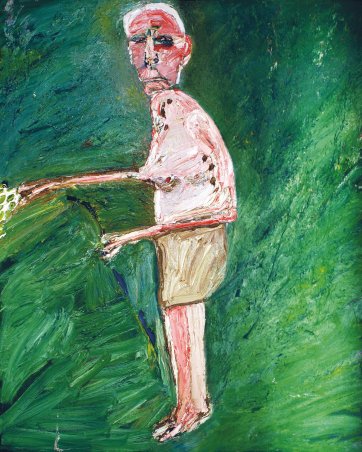

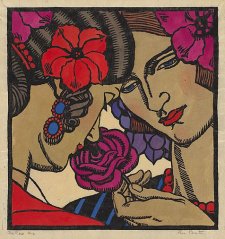

People in Idle hours are not all taking a break from constructive activity; but they are almost all taking a break from self-consciousness, angst and restlessness. Idle hours is an exhibition of images of contentment – images of people disconnected, in some cases, and concentrating, in other, but all of them at ease with who and where they are. Most of them are at home. In depicting family, friends and strangers doing nothing much, artists enter into an extended pact of quietude with their sitters. Brought together, such works trial the tranquil circumstances of their creation into the gallery space; contemplating the painting, prints and drawings in the exhibition, the viewer is drawn into the silent stillness of the situations depicted.

Idle hours takes its name not only from the theme, but from the layout of the show – the works of which, regardless of the year in which they were made, are hung according to the time of day or night that they depict. The first room of Idle hours contains pictures of people waking up, breakfasting and enjoying the sun. By the entrance to the second room, the first person has fallen into an after-lunch siesta; others work through a basket of ironing, pick up their sewing, or sit down to afternoon tea. As the afternoon lengthens, people enjoy a beer, ease into a bath and watch television. In the last room, as night falls and deepens, others prepare dinner, put on a record or settle in for some serious talking. Moving through the span of a waking day, Idle hours is an exhibition about the quality of light as well as one that emphasises the commonality of middle-class Western experience.

Almost nobody is smiling in Idle hours. Some of the men and women depicted are so self-contained that we might question whether they feature in portraits or still-life compositions. But the human presence in the works means that many of them seem to invite us to listen as well as look; if we do so, what we will hear is a limpid stillness. Idle hours is balm for increasing numbers of us who wonder why we work longer hours than our parents and grandparents; why we seldom finish reading the books piled by our beds; why we spend so much time in the office and shopping mall. It invites us to ask when we began to accelerate; to become little more than a tangle of traits, habits and needs that we don’t admire in others. It is a show about self-possession, constructive routines and close attention to loved ones – about contentment, and complaisance. On reflection, in fact, it is a show of happy portraits.