The idea of animated portraits would not surprise any student of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. There, the cliché of portraiture is fulfilled and the eyes in each portrait literally follow you around the room, and sometimes more. The humour and surprise from these portraits derives from the fact that in a house of magic, portraits can defy the expectation of a conventional static representation of a sitter: they move; they are animated. The magic of animation allows the animators in the exhibition hosted by the National Portrait Gallery to confront and confound the idea that a sitter must sit still. Its not that fidgeting is encouraged but more the recognition that agitated line can prompt a positive and aesthetic reaction that is different from a conventional portrait built with stationary elements.

There is a renewed interest in animation with the advent of adult orientated cartoons such as South Park, The Simpsons, Futurama, King of the Hill, Family Guy, Ren and Stimpy, Happy Tree Friends, Stripperalla, and others on television and the popularity of graphic novels. Recent films based on comic book heroes (though not all strictly animated) such as Batman, Hellboy, 300, The Incredibles Sin City and the like (Wikipedia lists 200 titles), also reinforce this fascination with artfully created characters. Only a few artists have made animations up until now, flip books being the simplest technique available to untrained illustrators until recently. Today, computers have made animation much less difficult for non-professionals to make and the rise in the number of animators working in Australia is coupled to the ease of creating moving images on screen.

It is the NPG’s first on-line exhibition, that is a virtual exhibition with out a physical presence in a gallery. In part this is the nature of the medium: it is ephemeral, exists only while being played and is dependent on technological support. An animated portrait can be near motionless but always has the potential to be lively, and noisy, to be undeniably contemporary and part of the connected age. This presents a particularly exciting moment for portraiture. The use of moving images will extend the notion of portraiture beyond traditional static portraits.. And the capacity for sound as part of the meaning of a portrait will also challenge standing tradition. The association with popular culture also distinguishes these portraits from others.

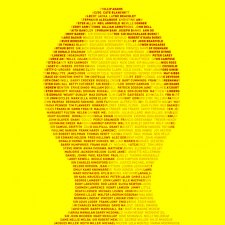

The exhibition showcases a variety of conceptual approaches and a host of different techniques, for example stop frame animation, collage, claymation and flash animation as well as 3D animation and other CGI techniques in two and three dimensions. The exhibition takes advantage of the capabilities and limitations of new, screen based technology. The concept of the self-portrait theme shifts the emphasis away from the sitter and on the power of the idea and the unique contribution of the technique to describe character and personality.

Rarely static and monolithic like conventional portraiture the animations in this exhibition make a virtue of their differences. Because there is no commitment to a single image, the self portraits appear anti monumental (though Rick Bull’s mystic animation has a monumental aspect) composed as they are of serial images, each ephemeral and liquid in transition, dependent on other images and working with sound or undercut by a sound track. The whole repertoire filmic devices are available to the animators, who can bring a whole new language to bear on portraiture.

These animators appear to have a higher commitment to emotion than conventional portraitists, or at least greater means to achieve it – by using sound and music, changing emotional expressions and colours, and the use of temporal manipulation. The animated self portraits maintain a high degree of the autographic and analytical quality of older art media as opposed to the mechanical surfaces of photography. When photography is used as source (as it is in the work of a number of the animators) the unnatural shorthand of the artist directed movement ensure that there is no mistaking this for reality. Artists are conscious of style and employ a very different aesthetic than conventional portraitists, often favouring approaches allied to graphic art. In creating their self portraits, the artists in Animated have maintained a commitment to humour. This may well reflect the subject matter as much as the medium. The artists have undercut a sober and serious self portrayal with hilarious self depreciation like Paul Oslo Taylor or ironic distance as does Anita Johnson. The artists have aimed to convey a satisfying visual argument: there is no striving for tour de force effects- and most of the works are technically simple and appropriate to the task.

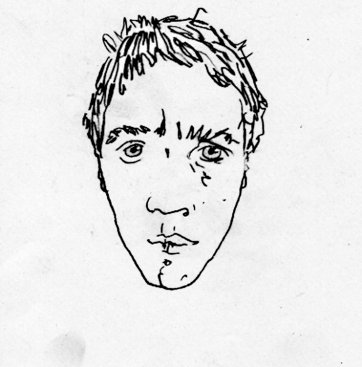

Ian Haig delights in a lo fi aesthetic, his technique and sound track matching perfectly the visceral and chaotic mask of his imagined visage. Haig has emphasised the corporeality of the human face as a mass of pores, openings, mobile flesh and unstable surfaces.

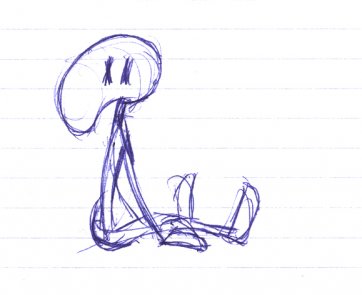

Rick Bull’s work is a piece of classic flash animation, coupling simple movements with a strong graphic approach, using uninflected colours and a restricted palette. This is a mystic and internal portrait, one that favours emotion rather than reason. Not surprising to learn that Bull (AKA Deepchild) is a musician whose prime medium is sound, so he used to expressing himself by association rather than by literal description.

Like Haig, Paul Oslo Davis considers his face as a site of entropy. His respectable veneer is a result of the constant and loving actions of his partner who keeps chaos at bay like leaning guy strong line, humorous comment. Gritty, hand drawn quality, animation par excellence as clearly hand drawn, shorthand, concentration on the essentials, only the vital parts are included.

Arlene Texta Queen is known for her witty portraits composed with strong clean lines. Her animation naturally extends her the powerful graphic quality of her drawings, exploiting the descriptive potential of line. Her beautiful drawing exudes a sexy, sly humour underscoring an enigmatic persona.

Matt Taylor plays on the cadavre exquis invented by the French Surrealists using turning pages to change the suite of faces that represent his alter egos. How can you record your own features when you can never actually see them and they are, in any case, constant changing, Taylor’s perception of self is created through the interplay between image, movement and personality.

In her delightful photo-based animation, Kate McCartney (AKA Kitty McCity) uses stopframe animation , as does Pia Borg. Despite the similarity of technique, both artists have produced racially different results. McCartney sees moments of her life defined by music and presents a self portrait as a music video clip. Borg situates her identity within ambiguous narratives and defines her portrait with atmospherics.

Jonathan Daw also uses photographic images, collaged one against the next to effect movement. Personal narrative of struggle tempered by hilarity of absurd life The Contextual Villains, Paul Mosig and Rachel Peachey have tackled the challenge of an animated double portrait. They combine photographic imagery with hand drawn elements. The friction between the two approaches echoes the fact that the artist portraits effectively defines each in terms of the other.

Troy Innocent’s self portrait is abstract. He has portrayed himself as a geometric cipher in a mathematically defined environment. Its not how you look but how you understand yourself in relation to your surroundings. Innocent has situated his avatar in a environment of signs and symbols, a metaphor of the artists exploring the an electronic humanity.

In contrast, Jo Boag’s soft had drawn animation is beautifully matched to the cosy domesticity of her life. Anita Johnson’s work also suggests intimacy but the surreal backdrop to her self portrait is quite disturbing.

London-based artist Tony Thorne uses 3D animation, picturing himself striding, forever catching up, across a fast moving world. Thorne sees himself as everyman locked in a never-ending struggle, a labour of Sisyphus. His life (and ours) makes the point, in an animation tinged with good humour and optimism, that what choice is there but to carry on?

It is almost a cliché to note the entomological root of the word ‘Animate’ – from the Latin Anima [breath; soul], that the task of animation is to give the breath of life to something or confer movement. However, animation, at least as practiced in this selection of self portraits is not more like life, but perhaps the reverse: more like art. The viewer is conscious of the artifice in the jiggle of lines, the selective focus and elimination of detail, the heightened aesthetic and the forced conformity of life to the artist’s style and manner that is utterly unreal. When the line between art and reality is confused, the enjoyment of the animator’s skill is diminished, witness the recent rotoscoped feature film, A Scanner Darkly 2006 that unashamedly starred real Hollywood actors Keanu Reeves, Robert Downey Jr. and Winona Ryder. The best art is a distillation from life and the artists in Animated have held a mirror to themselves and recorded what they feel as well as what they see. These animated self portraits offer an insight into the attitude each artist has of themselves, as well as recording an emotional and physical likeness.

Michael Desmond and Gillian Raymond