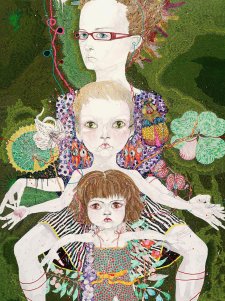

Ellen Stirling’s dark eyes, rosy cheeks and alabaster pallor might be the most striking features of her portrait. But the true source of her attractions lay beneath the surface, beyond the reach of painterly skill and flattery.

Naval officer James Stirling was purportedly smitten the first time he clapped eyes on Ellen Mangles. He was in his late twenties; she was thirteen. Ellen was later described as ‘adventurous, not yet introduced to the simpering ways of high society’, preferring outdoor pursuits such as horse-riding to ‘dancing or conversing sentimentally with the beaux’. They were wed in 1823, on Ellen’s sixteenth birthday. In 1829 they sailed for Perth, Western Australia, James having been appointed the new colony’s lieutenant-governor. A simpering wallflower simply wouldn’t do in such a place, and throughout the Stirlings’ eight-year post Ellen impressed with her feminine attributes and gift for combining them with an absence of affectation. Beauty, elegance, grace: such traits comprised the behavioural code she was expected to observe. Yet the code was easily undermined on the peripheries of empire – pointing to what it was about Ellen that must have so captivated Stirling in the first place.